I’d like to write about our forthcoming book, Lafcadio Hearn’s Insect Literature. Actually, I don’t want to write about Insect Literature so much as I’d like an excuse to tell you how a Swan River Press book gets put together. I’m inordinately proud of this one too, because it has so many meaningful features worked into its design. I’ll just start at the beginning.

I’d like to write about our forthcoming book, Lafcadio Hearn’s Insect Literature. Actually, I don’t want to write about Insect Literature so much as I’d like an excuse to tell you how a Swan River Press book gets put together. I’m inordinately proud of this one too, because it has so many meaningful features worked into its design. I’ll just start at the beginning.

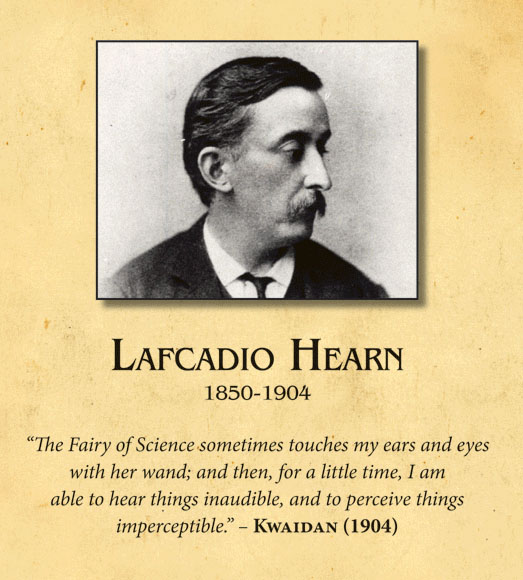

For a long time Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904) had been on my mental list of Irish authors I’d like to showcase. But I’d always hesitated as much of his work is already widely available and in inexpensive editions. I wanted something special, a project that was unique and interesting. A book only Swan River Press could publish. Enter Anne-Sylvie Homassel.

Anne-Sylvie brought Insect Literature to my attention a good while back. The earliest reference to it in our correspondence that I can find dates back to November 2013. After our initial conversation, the idea sat at the back of my brain until sometime in 2014 when I learned from my friend John Moran that the Little Museum of Dublin would be mounting a major exhibition on the life and works of Hearn in the autumn of 2015. Work promptly started on the project so that the book would be ready in time for the celebrations.

So what is Insect Literature? Very briefly: Insect Literature is a posthumous collection of Hearn’s essays and stories on insects originally published by Hokuseidō Press in 1921. It was edited by one of Hearn’s former students, Masanobu Ōtani, as part of a multi-volume bilingual (Japanese/English) “Hearn Memorial Translations” series.The original volume contains ten insect-related texts—for Swan River’s new edition Anne-Sylvie has added another ten. You can buy a copy here, if you’d like!

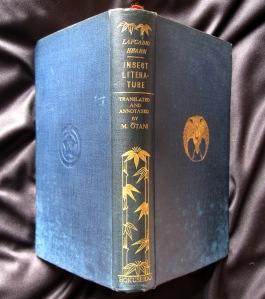

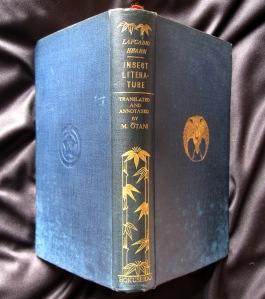

The first order of business was track down a first edition copy. The reason I wanted to at least see a copy was because I like to incorporate elements from the original publications as part of Swan River’s designs. Apparently, as I quickly learned, Insect Literature is a rare enough oul’ book. I could find mentions of it in online catalogues and it is listed in P.D. & Ione Perkins’s bibliography (and in the collections of two university libraries—one in Australia, the other in Kentucky), but nowhere could I find copies for sale, or even evidence of copies that had been for sale.

The first order of business was track down a first edition copy. The reason I wanted to at least see a copy was because I like to incorporate elements from the original publications as part of Swan River’s designs. Apparently, as I quickly learned, Insect Literature is a rare enough oul’ book. I could find mentions of it in online catalogues and it is listed in P.D. & Ione Perkins’s bibliography (and in the collections of two university libraries—one in Australia, the other in Kentucky), but nowhere could I find copies for sale, or even evidence of copies that had been for sale.

There’s an interesting reason for the scarcity of this book though. On 1 September 1923, Tōkyō was devastated by the Great Kantō Earthquake. The destruction was total and the subsequent fires engulfed much of Tōkyō, destroying Hokuseidō’s warehouses and stock in the process. But that didn’t stop me from occasionally trawling the internet, hoping a copy might turn up.

As luck would have it, one evening in early spring 2015, about seven or eight pages deep into a Google search, I found an entry for Insect Literature on a French auction website. The listing, which had no bids, had been posted in 2013. What were the chances it was still available? But it was the first lead I’d seen, so I had to try. I promptly wrote to the auctioneer, fully not expecting a reply. Or if I got a response, that I would be told it had already been sold. Or had been lost. Or . . .

But I did get a reply, the book was still available, and after a nervous two-week wait for something to go wrong, Insect Literature arrived safely here at our offices in Dublin. (If anyone else finds another copy, I’d love to know.)

It’s a beautifully designed book with English on the versos and Japanese on the facing rectos. The blue buckram cover bears Hearn’s personal seal stamped in gold. It’s a heron. Get it? But let’s move on to what I really want to talk about: the design of our new edition.

It’s a beautifully designed book with English on the versos and Japanese on the facing rectos. The blue buckram cover bears Hearn’s personal seal stamped in gold. It’s a heron. Get it? But let’s move on to what I really want to talk about: the design of our new edition.

So the text first. The original edition features Japanese translations by the editor Masanobu Ōtani. While I couldn’t reprint the translated text as in the original, I felt it important to preserve the sense of the bilingual in our edition. The best way to do this would be to print the Japanese titles for each story above their English counterparts. The resulting layout looked pretty good, but we had one slight problem. While Ōtani provided translated titles for the original ten texts in Insect Literature, we had to go searching for translations for the additional titles. For this I went to Rebecca Bourke and my old friend Edward Crandall. They first checked for any existing title translations (which they found for the likes of “Gaki” and “The Dream of Akinosuké”). But when no existing title could be found, new translations had to be created.

In addition to the translated titles, we also included M. Ōtani’s brief forward; perhaps not particularly illuminating, but it felt an intimate part of the original book, and thus warranted inclusion. Another interesting element in the first edition is the reproduction of a handwritten letter from Hearn’s friend Mitchell McDonald praising the late author. (McDonald also served as Hearn’s literary executor; unfortunately he died in the Great Kantō Earthquake.) In the end we decided to leave the letter out of the book because it didn’t add much to the immediate context of Insect Literature. However, we did make the text available on the website, which you can read here.

In addition to the translated titles, we also included M. Ōtani’s brief forward; perhaps not particularly illuminating, but it felt an intimate part of the original book, and thus warranted inclusion. Another interesting element in the first edition is the reproduction of a handwritten letter from Hearn’s friend Mitchell McDonald praising the late author. (McDonald also served as Hearn’s literary executor; unfortunately he died in the Great Kantō Earthquake.) In the end we decided to leave the letter out of the book because it didn’t add much to the immediate context of Insect Literature. However, we did make the text available on the website, which you can read here.

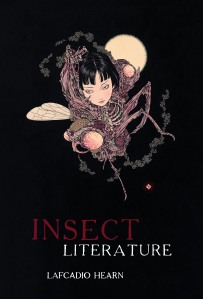

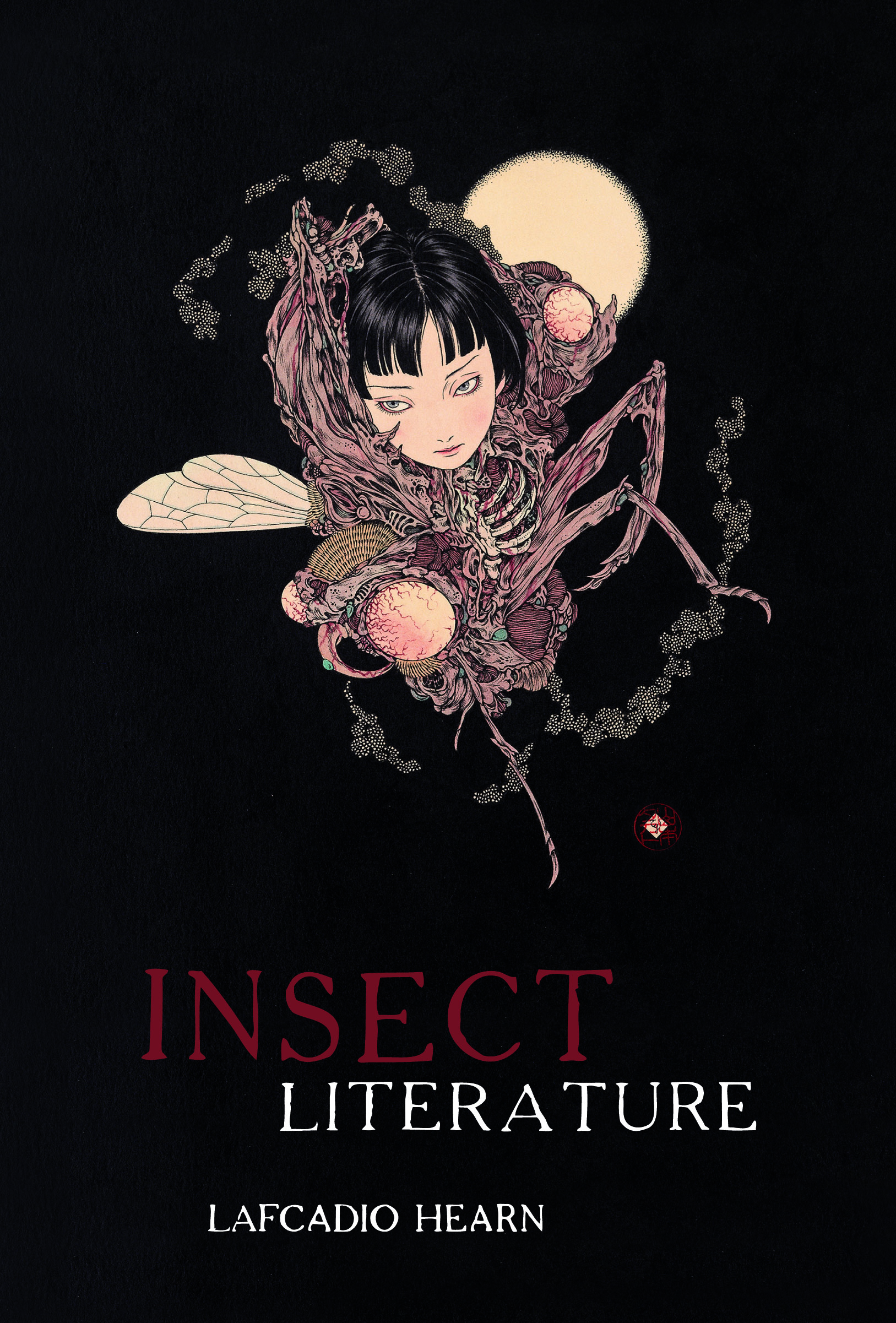

Which brings us to the dust jacket. Here it is in full view. You can click on the image below if you want to get a better look at it.

The first time I saw Takato Yamamoto’s “Bug”, I knew instantly that I wanted it on the cover of our new edition. I don’t think I ever really had a second choice. Very much in the spirit of Hearn, this project was destined to be international. Anne-Sylvie’s in France, I’m in Ireland, Ken is in England, Xand is in Germany, Jim and Meggan are in America. All I had to do now was track down Mr. Yamamoto in Japan. It took some doing, but I eventually managed to get in touch with his agent, who kindly allowed for its use. And there it is buzzing beautifully on the cover.

Now have a closer look at the jacket. See the title and the author’s name there on the front panel? Our designer, Meggan Kehrli, lifted that font from the original title page of Insect Literature. (This is a trick we also did for the cover of our edition of Thomas Leland’s Longsword, which she lifted from the title page of the 1762 edition). The same font gets used again on the spine as well as on the front flap. It’s subtle and not everyone will notice, but I like knowing it’s there anyway. It somehow adds something to the book for me.

Now have a closer look at the jacket. See the title and the author’s name there on the front panel? Our designer, Meggan Kehrli, lifted that font from the original title page of Insect Literature. (This is a trick we also did for the cover of our edition of Thomas Leland’s Longsword, which she lifted from the title page of the 1762 edition). The same font gets used again on the spine as well as on the front flap. It’s subtle and not everyone will notice, but I like knowing it’s there anyway. It somehow adds something to the book for me.

While doing bibliographic research on the original publications of the various texts that comprise Insect Literature, I consulted a number of other first editions, many of which contained illustrations. While we didn’t use all of what was available, we certainly included a good sampling of the more impressive ones. There are four really lovely ones by Genjiro Yeto that originally appeared in Kottō (1902). Originally I wasn’t going to include any illustrations, but the more I looked at them, the more I wanted them there in our new edition.

While doing bibliographic research on the original publications of the various texts that comprise Insect Literature, I consulted a number of other first editions, many of which contained illustrations. While we didn’t use all of what was available, we certainly included a good sampling of the more impressive ones. There are four really lovely ones by Genjiro Yeto that originally appeared in Kottō (1902). Originally I wasn’t going to include any illustrations, but the more I looked at them, the more I wanted them there in our new edition.

My favourite, though, are the two little guys on the title page. I found them among the pages of Exotics and Retrospectives (1898), where they originally appeared as illustrations for the sublime essay “Insect-Musicians”. (Another insect-musician appears on the spine of the PPC pictured below.)

My favourite, though, are the two little guys on the title page. I found them among the pages of Exotics and Retrospectives (1898), where they originally appeared as illustrations for the sublime essay “Insect-Musicians”. (Another insect-musician appears on the spine of the PPC pictured below.)

The title page could have been different though. I very nearly put Hearn’s heron there instead. Much as I liked the idea, and it would certainly be in keeping with the first edition, it seemed vaguely silly to put a bird on the title page of a book called Insect Literature. The heron will have to wait until the next Hearn book we do.

On the rear flap of the jacket you’ll see a photo of Hearn standing beside a seated school boy. This rare photo appeared as the frontispiece in Insect Literature, and therefore made perfect sense to use for our edition’s author photo. The school boy also happens to be Insect Literature‘s original editor and translator, Masanobu Ōtani, making this photo even more appropriate and special.

And then there’s the PPC. As with the jacket, you can click on the below image to get a closer look.

This is the image that’s printed directly onto the boards underneath the dust jacket. The printed PPC has been a feature of Swan River Press books since the beginning. I always thought that space under a dust jacket was a bit wasted, especially on mass market hardbacks, which tend to just reprint the jacket design. That’s boring. I like giving the reader something to discover.

So the above composite image for the PPC was created by Swan River’s long-time designer Meggan Kehrli. (When I say long time, I mean she’s had a hand in every book right from the start.) The pale cream field on which the insects sit is Meggan’s own handiwork with paper, brush, and dab of watercolour. The dragon-flies are illustrations from “Dragon-flies”, which appeared in A Japanese Miscellany (1901). The cicadae were taken from “Sémi” in Shadowings (1900), while that grasshopper fella and the little guy on the spine are both “Insect-Musicians” from Exotics and Retrospectives (1898). I love how they’re arranged as if a Victorian entomological display. Meggan has created something entirely new with these specimens from the past.

And now for the calligraphy on the spine, which was provided by Yaeko Crandall. The top bit says “Insect Literature“, while the bottom is “Koizumi Yakumo” (Hearn’s Japanese name). Normally on PPCs I don’t like to include any text. But because I wanted another nod to Insect Literature‘s original bilingualism, I thought we could bend the rule just this once. I think it looks great.

Finally, see that little red butterfly on the spine? It just fell into place there, mirroring the ornament we use on all Swan River jacket spines. Anyway, that little butterfly is from the very last page of Hokuseidō Press’s edition of Insect Literature.

And that’s about it. At least all I wanted to write about the sort of things that can go into a Swan River Press book design. Not all our books are as extensively layered with meaning as Insect Literature, but for Hearn we had such a wealth of resources available, why not make use of them?

Of course other work went into the making of this book too, less visible, but no less important: Ken McKenzie’s meticulous typesetting (for this book he had to deal with three languages!), Xand Lourenco’s transcribing (again, in three languages), Jim Rockhill’s proofreading (Jim’s another one of Swan River’s secret weapons—he keeps the words classy), not to mention Gentleman John Moran, who lent his Hearn expertise at nearly every turn (he’s also involved in the Little Museum exhibition). And of course Anne-Sylvie Homassel, who not only netted this whole project, but provided a fine introduction for our new edition.

Lafcadio Hearn is an author whose work you can immerse yourself in. His talent as a prose stylist is such that nearly any topic he decides to put his pen to is rendered fascinating and otherworldly. Immersing myself in Hearn’s world is exactly what I did as we put this book together. Through the whole process I read biographies about Hearn, scoured bibliographies, consulted books in the National Library, and just sort of snooped around to see what might turn up . . . it was really good fun!

As I said at the beginning of this article, I’m quite fond of this book. Many hours of work went into making our new edition of Insect Literature. I hope people enjoy it. Thank you for reading.

“The Fairy of Science sometimes touches my ears and eyes with her wand; and then, for a little time, I am able to hear things inaudible, and to perceive things imperceptible. – Kwaidan (1904)

“The Fairy of Science sometimes touches my ears and eyes with her wand; and then, for a little time, I am able to hear things inaudible, and to perceive things imperceptible. – Kwaidan (1904) Collections

Collections Unfortunately our sole Lafcadio Hearn title,

Unfortunately our sole Lafcadio Hearn title,  A good while back I posted the image of a poster designed by myself and long-time Swan River conspirator Jason Zerrillo. It features a line-up of Ireland’s most recognisable and possibly most influential writers of fantastic literature. I explained the impetus for the poster’s creation in an earlier

A good while back I posted the image of a poster designed by myself and long-time Swan River conspirator Jason Zerrillo. It features a line-up of Ireland’s most recognisable and possibly most influential writers of fantastic literature. I explained the impetus for the poster’s creation in an earlier

It’s a beautifully designed book with English on the versos and Japanese on the facing rectos. The blue buckram cover bears Hearn’s personal seal stamped in gold. It’s a heron. Get it? But let’s move on to what I really want to talk about: the design of our new edition.

It’s a beautifully designed book with English on the versos and Japanese on the facing rectos. The blue buckram cover bears Hearn’s personal seal stamped in gold. It’s a heron. Get it? But let’s move on to what I really want to talk about: the design of our new edition.

My favourite, though, are the two little guys on the title page. I found them among the pages of Exotics and Retrospectives (1898), where they originally appeared as illustrations for the sublime essay “Insect-Musicians”. (Another insect-musician appears on the spine of the PPC pictured below.)

My favourite, though, are the two little guys on the title page. I found them among the pages of Exotics and Retrospectives (1898), where they originally appeared as illustrations for the sublime essay “Insect-Musicians”. (Another insect-musician appears on the spine of the PPC pictured below.)