“In Ireland we have a national apathy about literature . . . It began to descend on us after we became self-governing; before that we were imaginative dreamers.”

— AE to Van Wyck Brooks, 10 October 1932

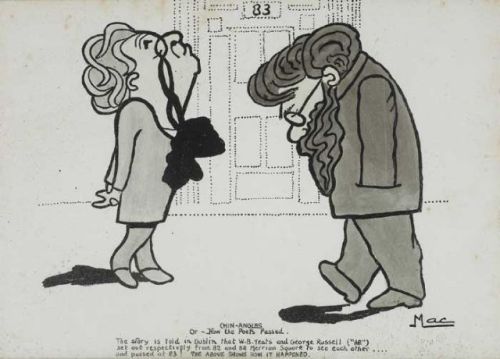

So wrote the poet, painter, and mystic George William Russell (1867-1935) — better known by his spiritual name AE — less than a year before he left Ireland after a lifetime working to enrich a nation he loved and dedicated himself to. Yet his vision of Ireland as an enlightened society was seemingly at odds with the mass desire for the cultural censorship and social conservatism that coincided with the birth of the Irish Free State.

Today, with the continuation of a crippling austerity policy — which includes the treatment of the arts as commodity, the considered monetisation of our public museums, financial cuts to arts funding, and the budgetary destitution of the National Library, among other similar injuries masquerading as common sense measures — one wonders just exactly how the arts are valued in a nation that still proudly sells itself as “the land of saints and scholars”.

Fifty years later, a sentiment similar to AE’s was echoed by author Mervyn Wall (1908-1997) in a fascinating interview (reprinted in this issue) in which he asserts that, “When the new Free State was set up, it settled down to very mundane things . . . since 1922 there has been no inspired leadership whatsoever, leadership that would say here is a small country starting off fresh and here is the opportunity to make something wonderful of it.” But instead of leaving Ireland, as so many of our luminaries did (and still do), Wall wrote a pair of brilliant fantasy novels, The Unfortunate Fursey (1946) and The Return of Fursey (1948), sharply satirising both Church and State — and though they tried, the Irish censors could find no specific reason to ban Wall’s books. Similarly acerbic, his 1952 novel, Leaves for the Burning, with its accumulation of exaggerated and improbable details, is often read as a satire, but as critic Robert Hogan points out, should be considered more of a realistic (“albeit one-sided”) depiction of post-war Ireland. Wall, incidentally, worked for the Arts Council from 1957-1975, and his legacy includes Ireland’s tax exemption for artists scheme, which I might add the current government occasionally talks of abolishing because of its perceived “cost to the taxpayer”. Many of Wall’s comments in this interview, though conducted over thirty years ago, feel just as relevant today.

Fifty years later, a sentiment similar to AE’s was echoed by author Mervyn Wall (1908-1997) in a fascinating interview (reprinted in this issue) in which he asserts that, “When the new Free State was set up, it settled down to very mundane things . . . since 1922 there has been no inspired leadership whatsoever, leadership that would say here is a small country starting off fresh and here is the opportunity to make something wonderful of it.” But instead of leaving Ireland, as so many of our luminaries did (and still do), Wall wrote a pair of brilliant fantasy novels, The Unfortunate Fursey (1946) and The Return of Fursey (1948), sharply satirising both Church and State — and though they tried, the Irish censors could find no specific reason to ban Wall’s books. Similarly acerbic, his 1952 novel, Leaves for the Burning, with its accumulation of exaggerated and improbable details, is often read as a satire, but as critic Robert Hogan points out, should be considered more of a realistic (“albeit one-sided”) depiction of post-war Ireland. Wall, incidentally, worked for the Arts Council from 1957-1975, and his legacy includes Ireland’s tax exemption for artists scheme, which I might add the current government occasionally talks of abolishing because of its perceived “cost to the taxpayer”. Many of Wall’s comments in this interview, though conducted over thirty years ago, feel just as relevant today.

Also in this issue you’ll find Kevin Corstorphine’s survey of a selection of stories by Cork-born author Fitz-James O’Brien (1826?-1862). O’Brien left Ireland at a young age, and eventually settled into a bohemian literary lifestyle in New York before perishing in the American Civil War. Corstorphine looks at O’Brien’s better known stories, like “What Was It?” and “The Diamond Lens”, and those less read but equally deserving of examination, such as “The Lost Room” and “A Dead Secret”. We’ve also got an essay by noted Stoker-scholar Elizabeth Miller, who considers in detail the 1901 abridged paperback edition of Dracula. Published during Stoker’s lifetime, and possibly even condensed by his own hand, Miller’s essay sheds just a little more light on the mind of the Dubliner who penned the most influential horror novel of all time. Finally, though Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s bicentenary celebrations are now over, here are two short, but important pieces by Richard Dury and James Machin that are simply too good to pass up: new discoveries that notably expand the ever-growing list of the Invisible Prince’s admirers.

Also in this issue you’ll find Kevin Corstorphine’s survey of a selection of stories by Cork-born author Fitz-James O’Brien (1826?-1862). O’Brien left Ireland at a young age, and eventually settled into a bohemian literary lifestyle in New York before perishing in the American Civil War. Corstorphine looks at O’Brien’s better known stories, like “What Was It?” and “The Diamond Lens”, and those less read but equally deserving of examination, such as “The Lost Room” and “A Dead Secret”. We’ve also got an essay by noted Stoker-scholar Elizabeth Miller, who considers in detail the 1901 abridged paperback edition of Dracula. Published during Stoker’s lifetime, and possibly even condensed by his own hand, Miller’s essay sheds just a little more light on the mind of the Dubliner who penned the most influential horror novel of all time. Finally, though Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s bicentenary celebrations are now over, here are two short, but important pieces by Richard Dury and James Machin that are simply too good to pass up: new discoveries that notably expand the ever-growing list of the Invisible Prince’s admirers.

A word should also be said about this issue’s cover painting, “The Princess on the Ridge of the World” by Pamela Colman Smith (1878-1951). Pixie, as she was known to her friends, was an accomplished artist who not only illustrated Bram Stoker’s final novel, Lair of the White Worm (1911), but in 1909 contributed the eighty drawings that adorn the iconic Rider-Waite-Smith tarot deck. The painting on the cover of this issue, which kindly comes to us from the Collection of John Moore, was a gift from Pamela Colman Smith to AE. An inscription on the back of the painting reads: “To AE, with all good wishes to you and yours for Christmas and the New Year and all time. Yours, Pixie. Xmas 1902.” Beside the inscription is a small drawing of a pixie. As a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Pamela Colman Smith was likely introduced to AE through their mutual friend W.B. Yeats. This is the first time “The Princess on the Ridge of the World” has been published.

A word should also be said about this issue’s cover painting, “The Princess on the Ridge of the World” by Pamela Colman Smith (1878-1951). Pixie, as she was known to her friends, was an accomplished artist who not only illustrated Bram Stoker’s final novel, Lair of the White Worm (1911), but in 1909 contributed the eighty drawings that adorn the iconic Rider-Waite-Smith tarot deck. The painting on the cover of this issue, which kindly comes to us from the Collection of John Moore, was a gift from Pamela Colman Smith to AE. An inscription on the back of the painting reads: “To AE, with all good wishes to you and yours for Christmas and the New Year and all time. Yours, Pixie. Xmas 1902.” Beside the inscription is a small drawing of a pixie. As a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Pamela Colman Smith was likely introduced to AE through their mutual friend W.B. Yeats. This is the first time “The Princess on the Ridge of the World” has been published.

AE’s comment regarding our national apathy toward literature—and art in general—is provocative and disheartening, and the natural instinct will be to deny it, pointing to one example or another of independent artistry or do-it-yourself creativity existing in Ireland today. And yes, AE’s comment was made nearly a century ago. But I do not think his assertion should be dismissed without first deep consideration tempered with honesty free from national pride.

However, given the gloominess of AE’s words at the start of this piece, I thought we might do well to end it with a comment he made to Seán Ó Faoláin in a letter from 1933, a decidedly more hopeful prescription from the man who helped shepherd into the world writings we now associate with Ireland’s literary identity.

“We have imagined ourselves into littleness, darkness, and ignorance, and we have to imagine ourselves back into light.”

Brian J. Showers

Rathmines, Dublin

17 March 2015

Order The Green Book 5 here.

“Editor’s Note” Brian J. Showers

“Fitz-James O’Brien: The Seen and the Unseen” by Kevin Corstorphine

“A Story-teller: Stevenson on Le Fanu” Richard Dury

“Arthur Machen and J.S. Le Fanu” James Machin

“Shape-shifting Dracula: The Abridged Edition of 1901″ Elizabeth Miller

“An Interview with Mervyn Wall” Gordon Henderson

Reviews

Digby Rumsey’s Shooting for the Butler (Martin Andersson)

Wireless Mystery Theatre’s Green Tea (Jim Rockhill)

Dara Downey’s American Women’s Ghost Stories in the Gilded Age (Maria Giakaniki)

J.S. Le Fanu’s Reminiscences of a Bachelor (Robert Lloyd Parry)

Charlotte Riddell’s A Struggle for Fame (Jarlath Killeen)

Karl Whitney’s Hidden City (John Howard)

“Notes on Contributors”