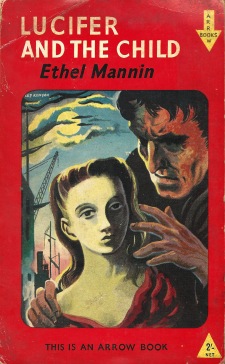

This is the story of Jenny Flower, London slum child, who one day, on an outing to the country, meets a Dark Stranger with horns on his head. It is the first day of August — Lammas — a witches’ sabbath. Jenny was born on Hallowe’en, and possibly descended from witches herself . . .

This is the story of Jenny Flower, London slum child, who one day, on an outing to the country, meets a Dark Stranger with horns on his head. It is the first day of August — Lammas — a witches’ sabbath. Jenny was born on Hallowe’en, and possibly descended from witches herself . . .

Once banned in Ireland by the Censorship of Publications Board, Lucifer and the Child is now available worldwide in this splendid new edition from Swan River Press featuring an introduction by Rosanne Rabinowitz and cover by Lorena Carrington.

Ethel Mannin (1900-1984) was a best-selling author who had written more than one hundred books but is virtually unknown today. Her output included fiction, journalism, short stories, travelogues, autobiography, and political analysis. All of her books have been out of print for decades — until now.

Born into a working-class family in South London, Mannin was a lifelong socialist, feminist, and anti-fascist. In the 1930s she organised alongside the Russian-born American anarchist Emma Goldman in support of the Spanish anarchosyndicalist forces and their struggle against Franco. Later, she agitated for the Indian independence movement along with her husband Reg Reginald. She was an advocate for African liberation movements and one of the few, even on the post-war left, who stood up for the rights of Palestinians. Iraqi critic and educator Ahmed Al-Rawi has described her as a post-colonial writer, which was unusual among British authors of the time.

In her lifetime Mannin was also known for her famous lovers, including Bertrand Russell and W. B. Yeats. In fact, it was the Yeats connection that had me trawling internet archives and second-hand bookshops while researching my tale “The Shiftings” — a ghost story exploring her relationship with the poet — for Swan River Press’s anthology The Far Tower: Stories for W. B. Yeats (2019). But I first discovered Ethel Mannin years ago, when I was a teenaged history obsessive with a special interest in labour and radical history. The figure of Mannin’s comrade “Red” Emma Goldman, described by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover as the “most dangerous woman in America”, held a powerful fascination for me. In the course of my reading I came across a vivid description of Goldman giving a speech, which was an extract from Mannin’s historical novel Red Rose (1941). This brought me to my local library looking for Mannin’s work.

While I couldn’t find Red Rose or anything about Mannin’s political activities, I did discover old editions of Venetian Blinds (1933) and Lucifer and the Child, which was first published in 1945. Venetian Blinds is a realist novel about the price paid for upward mobility, starting with the excitement of market day on Battersea’s Lavender Hill and ending with loneliness in the suburbs. It reminded me of early George Orwell novels such as A Clergyman’s Daughter (1935) and Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936), which were also about crossing class lines — albeit in the opposite direction.

After the relatively straightforward social narrative of Venetian Blinds, the ambiguous supernaturalism of Lucifer and the Child was a surprise. It is a story of witchcraft — or is it? I already had an interest in supernatural fiction but did not expect to find it in this context. Set mainly in the crowded streets of 1930s East London, the story begins when young Jenny Flower strays from a school outing in the countryside where she encounters a Dark Stranger. He could be Lucifer, or he could simply be a very imaginative and charismatic sailor.

In a passage reminiscent of Arthur Machen’s “The Great God Pan” (1894) Mannin portrays the wonder and absolute awe of a city child encountering the forest for the first time: “Sometimes there were breaks in the bird-song and then everything was very still, as though every leaf of all the millions was holding its breath and waiting, and you also waited and listened and heard your own heart beating.”

While observing a dragon-fly Jenny discovers that she is not alone. A Dark Stranger has also been watching; he steadies her as she reels in surprise at its take-off. All adults had been the enemy to her but this one is “the bringer of new things”. For the first time, she sees a life beyond her council estate, her school, and a family that does not know what to make of her. A new world opens up, one where she potentially wields power. Jenny is ushered into the “Goetic life”, a process that evokes another noted work by Machen: “The White People” (1904) in which a curious girl is initiated by her nurse into dark ceremonies and the “most secret secrets” of the countryside.

Similarly, the Dark Stranger introduces Jenny to fairy rings in the grass and tells her how the Little People made them by dancing in the moonlight. He shows her a big yellow toad under a boulder. He reveals deadly nightshade, witches’ bane, hemlock, poisonous mushrooms. He spins her tales of tree-witches and wood-spirits, nymphs and dryads, fauns and satyrs. She also comes to learn that she might be descended from two sisters burned at the stake many centuries ago.

Similarly, the Dark Stranger introduces Jenny to fairy rings in the grass and tells her how the Little People made them by dancing in the moonlight. He shows her a big yellow toad under a boulder. He reveals deadly nightshade, witches’ bane, hemlock, poisonous mushrooms. He spins her tales of tree-witches and wood-spirits, nymphs and dryads, fauns and satyrs. She also comes to learn that she might be descended from two sisters burned at the stake many centuries ago.

Jenny is a solitary child who joins in the noisy games of the other children but does not have any true friends among them. She would rather spend time with Old Mother Beadle in Ropewalk Alley. Regarded as a witch by the local children, Mrs. Beadle supplements her pension by telling fortunes and selling concoctions of herbs to induce abortions. And in this capacity, she also guides Jenny into a world of magic.

Meanwhile, Jenny’s family views Mrs. Beadle as a bad influence. So too does Marian Drew, a teacher who takes an interest in her pupil and aims to “save” her from a descent into the irrational and ultimately evil “Goetic life”. Though Marian is a vicar’s daughter she’s not entirely straitlaced. She holds progressive notions of educational freedom and creativity, perhaps reflective of Mannin’s interest in the Summerhill school of A. S. Neil, who advocated a libertarian education system in contrast to the more rigid teaching of the time.

Marian and the Dark Stranger form a relationship characterised by sharp physical attraction and equally intense debate. He asks Marian: “Do you really know where reality ends and fantasy begins? Are you quite sure that the images of your mind have no reality?” Indeed, themes regarding the transcendent and the commonplace run throughout the novel, and at one point he says to Marian: “Another drink and you may begin to understand that the supernatural is merely the natural plus.”

Lucifer and the Child is the only full-length work of speculative fiction from Mannin, who usually described herself as an atheist and rationalist. However, she was also a journalist, a seeker of curiosities and always keen to investigate. In one of her many volumes of autobiography, Privileged Spectator (1939), Mannin recollects a visit to a swami that Yeats admired. “For my part I was willing to try at least once my vibrations on a higher plane.” She gives a scathing account of her meeting with a well-fed, well-dressed individual expounding on the virtues of poverty. She had little time for mysticism or the pomp that often surrounded it.

Yet a powerful charge of the numinous and strange runs through Lucifer and the Child, despite its realism — or possibly because of it. Like Machen, Mannin also takes inspiration from London itself as well as the natural world. “Its interminable greyness and its high dockyard walls can make it as oppressive as a prison, but it has its moments — the occasional crumbling grace of a Georgian doorway, the sudden impression of a ship crossing the road as it moves into a basin, the unexpectedness of a lamp bracket jutting from a wall, of a capstan marooned in an alleyway, of funnels thrusting up at the ends of streets, and always the smell of the river with its faint, fugitive hint of the sea.”

Within this evocative cityscape we find a toad that is “strange and unknowable, like the moon” and step into Mrs. Beadle’s house: “Ordinariness stopped outside. The dilapidated door opened on to a new world. The world to which she belonged.” And in one of his arguments with Marian, the Dark Stranger suggests how the “spirit of the past” haunts people and places; a kind of spiritualism without the supernatural that would now strike a chord with modern psychogeographers.

The novel even touches on cosmic horror: “Enchantment was for her the deep forest through which she moved with deadly nightshade in her hand and an adder at her foot; it was her head upon the shoulder of the Dark Stranger, and starless night and the hunting cry of the owl; it was earth-light on the moon and no shade from the sun, and no living thing in the desolate volcanic wastes, and loneliness unutterable, the loneliness of space and dead worlds and infinity.”

Meanwhile, a dry humour underlies much of the narrative. For example, Marian’s thoughts about two do-gooding colleagues: “She reached the point at which she felt that if either of them referred once more to ‘the paw’, when speaking of the working classes, she would scream . . . ” I also chuckled when reading about the pious antics of local “cadets” joined by Jenny’s brother Les, who dedicates himself to marching and playing trumpet with them. “At the hall the cadets learned ‘First Aid’ and ‘Signalling’; they also did ‘physical jerks’, and took turns on the parallel bars and the ropes. Before they left, Mr. Wilson, their group-captain, a pale young man who was the Sunday-school superintendent, gave them a little talk on manliness and uprightness, clean thoughts and tongues, and the avoidance of something vaguely referred to as ‘bad habits’, and then they marched home again.” Such light-hearted observations grow darker as in the story’s background fascism continues to rise and conflict engulfs the world in the “sinister year 1936, with the dress-rehearsal for the coming world-war taking place in Spain”.

Mannin had been active in groups such as Workers Relief for the Victims of German Fascism and the Spanish Medical Aid Society. Looking back from the mid-1940s — she finished writing Lucifer and the Child in 1944 — 1936 indeed must have seemed an ominous turning point. And though the novel is rooted in the everyday lives of its characters, Mannin shows us that world events are never far away. She makes this connection explicit when Marian tells the cadet captain that she disapproves of “encouraging militarism” and boys “playing at soldiers” instead of creatively expressing themselves as individuals. Marian warns: “It’s only a few steps further on in this direction before they’re wearing jackboots — actually and spiritually!”

Mannin was a contradictory woman shaped by contradictory times, a prolific writer who produced an odd and imaginative book so unlike her others. Lucifer and the Child remains a rich portrayal of inter-war London and an engaging story of a girl who sought to escape it through myth and magic. And at the end of the book, the reader is left with another question: is the Dark Stranger really so “dark” after all? Or is he instead the “bringer of light”, a source of new things and knowledge in a world beset by evil far greater than any mischief wrought by a mythological fellow with horns? In effect, Lucifer and the Child is a story about the desire for a different life than the one we’re allotted and the extraordinary measures some may take to move beyond it.

“There is never any name for the impact of strangeness on the commonplace, that je ne sais quoi that ripples the surface of everydayness and sets up unaccountable disturbances in the imagination and the blood,” Mannin writes. With this sensibility Lucifer and the Child will at last be recognised as a classic of strange fiction and a work to be enjoyed by contemporary lovers of the genre.

Rosanne Rabinowitz

March 2020

Buy a copy of Lucifer and the Child.

Rosanne Rabinowitz lives in South London, an area that Arthur Machen once described as “shapeless, unmeaning, dreary, dismal beyond words”. In this most unshapen place she engages in a variety of occupations including care work and freelance editing. Her novella Helen’s Story was shortlisted for the 2013 Shirley Jackson Award and her first collection of short fiction, Resonance & Revolt, was published by Eibonvale Press in 2018. She spends a lot of time drinking coffee — sometimes whisky — and listening to loud music while looking out of her tenth-floor window. rosannerabinowitz.wordpress.com

At that time B. M. Croker was only remembered (by a shrinking number of admirers) as a once-popular bestselling novelist. Her supernatural tales had sunk into total neglect, and none had ever been revived in anthologies (not even by Hugh Lamb or Peter Haining).

At that time B. M. Croker was only remembered (by a shrinking number of admirers) as a once-popular bestselling novelist. Her supernatural tales had sunk into total neglect, and none had ever been revived in anthologies (not even by Hugh Lamb or Peter Haining).

Following common tradition as a Victorian soldier’s wife, Bithia accompanied her husband to India, where he served for several years in Madras and Burma. They had one child, Gertrude Eileen (always called “Eileen”). They later lived in Bengal, and at a hill-station in Wellington (where many of her early stories were written), very similar to the one described in “To Let”.

Following common tradition as a Victorian soldier’s wife, Bithia accompanied her husband to India, where he served for several years in Madras and Burma. They had one child, Gertrude Eileen (always called “Eileen”). They later lived in Bengal, and at a hill-station in Wellington (where many of her early stories were written), very similar to the one described in “To Let”.

My own experience with running

My own experience with running

On this day, 23 October 1869, readers of All the Year Round, edited by Charles Dickens, may well have been unprepared for a chilling tale of paranoia and despair that commenced in Mr. Dickens’s weekly journal. That story was “Green Tea”, and though it was originally published anonymously, it was penned by the Dublin writer Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu.

On this day, 23 October 1869, readers of All the Year Round, edited by Charles Dickens, may well have been unprepared for a chilling tale of paranoia and despair that commenced in Mr. Dickens’s weekly journal. That story was “Green Tea”, and though it was originally published anonymously, it was penned by the Dublin writer Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu. “Green Tea” was collected (along with Carmilla”) in Le Fanu’s most famous volume, In a Glass Darkly (1872), one of the author’s final books before he died in February of 1873. “Green Tea” has since become a staple of horror anthologies, gaining admirers from Dorothy L. Sayers to V. S. Pritchett.

“Green Tea” was collected (along with Carmilla”) in Le Fanu’s most famous volume, In a Glass Darkly (1872), one of the author’s final books before he died in February of 1873. “Green Tea” has since become a staple of horror anthologies, gaining admirers from Dorothy L. Sayers to V. S. Pritchett. That same year I asked Reggie Chamberlain-King of Belfast’s Wireless Mystery Theatre if he would adapt “Green Tea” as a radio drama. He did this, and the piece debuted at Toner’s Pub that August. I’d been searching for an excuse to record this wonderful adaptation, and when work on the new edition began, an opportunity had finally manifested. Each copy of our new edition of Green Tea will be issued with a CD of this magnificent recording.

That same year I asked Reggie Chamberlain-King of Belfast’s Wireless Mystery Theatre if he would adapt “Green Tea” as a radio drama. He did this, and the piece debuted at Toner’s Pub that August. I’d been searching for an excuse to record this wonderful adaptation, and when work on the new edition began, an opportunity had finally manifested. Each copy of our new edition of Green Tea will be issued with a CD of this magnificent recording. Rounding out the volume, Jim Rockhill and myself once again teamed up to write a pair of afterwords to explore the publication history and contemporary reception of “Green Tea”. We had previously done the same for Reminiscences of a Bachelor. Rockhill has long worked as a Le Fanu scholar, with perhaps his greatest achievement being a three-volume complete stories of Le Fanu, published by Ash Tree Press (2002-2005). It was great fun looking at “Green Tea” in depth. As always, we hope you find our scholarship illuminating, possibly even useful to your own explorations.

Rounding out the volume, Jim Rockhill and myself once again teamed up to write a pair of afterwords to explore the publication history and contemporary reception of “Green Tea”. We had previously done the same for Reminiscences of a Bachelor. Rockhill has long worked as a Le Fanu scholar, with perhaps his greatest achievement being a three-volume complete stories of Le Fanu, published by Ash Tree Press (2002-2005). It was great fun looking at “Green Tea” in depth. As always, we hope you find our scholarship illuminating, possibly even useful to your own explorations. Further instalments of “Green Tea” were published in All the Year Round over the subsequent three weeks in 1869: 30 October, 6 November, and 13 November. While you may have read this story before, we hope you’ll make time this season to return to its pages. For “Green Tea” Le Fanu holds no punches: exploring as he does the absolute limits of a man dogged by a fiend from hell, caught in the enormous machinery of a malignant universe. This is no cosy ghost story, no pleasing terror. The climax in “Green Tea” remains one of the bleakest in all of supernatural literature.

Further instalments of “Green Tea” were published in All the Year Round over the subsequent three weeks in 1869: 30 October, 6 November, and 13 November. While you may have read this story before, we hope you’ll make time this season to return to its pages. For “Green Tea” Le Fanu holds no punches: exploring as he does the absolute limits of a man dogged by a fiend from hell, caught in the enormous machinery of a malignant universe. This is no cosy ghost story, no pleasing terror. The climax in “Green Tea” remains one of the bleakest in all of supernatural literature. Conducted by Michael Dirda, © February 2018

Conducted by Michael Dirda, © February 2018 MD: I think all readers are interested in the writing and reading habits of favourite authors. Are you a quick study either as reader or writer? Your prose is remarkably clear, eerily effective, but seldom flamboyant. Does it come easily to you or is it the result of determined polishing and buffing. For instance, can you tell us about the gestation and development of the new collection’s first story, “Night Porter”? Aspects of it reminded me of L. P. Hartley’s classic, “A Visitor from Down Under”, while its ending is almost as enigmatic as one of Aickman’s stories.

MD: I think all readers are interested in the writing and reading habits of favourite authors. Are you a quick study either as reader or writer? Your prose is remarkably clear, eerily effective, but seldom flamboyant. Does it come easily to you or is it the result of determined polishing and buffing. For instance, can you tell us about the gestation and development of the new collection’s first story, “Night Porter”? Aspects of it reminded me of L. P. Hartley’s classic, “A Visitor from Down Under”, while its ending is almost as enigmatic as one of Aickman’s stories. Machen is very different. He is a magician with words. His love of the countryside and his fascination for the city both resonated with me when I left rural Sussex aged eighteen for the city of Sheffield, and his work still moves me profoundly. He has his faults as a writer (characterisation, mainly), but this is more than made up for by the depth of his vision and the power of his lyricism. There is an inherent humanity in Machen that I don’t find in Aickman.

Machen is very different. He is a magician with words. His love of the countryside and his fascination for the city both resonated with me when I left rural Sussex aged eighteen for the city of Sheffield, and his work still moves me profoundly. He has his faults as a writer (characterisation, mainly), but this is more than made up for by the depth of his vision and the power of his lyricism. There is an inherent humanity in Machen that I don’t find in Aickman. I’ve long been a fan of checklists, indicies, bibliographies, literary guides, and genre studies. From Lovecraft’s Supernatural Horror in Literature to E.F. Bleiler’s Guide to Supernatural Fiction, and many more besides. One can spend hours immersed in these books, discovering new avenues for exploration and making mental notes on obscure titles to look out for. My shelves groan with these sorts of volumes, and despite severe bowing in some places, I don’t regret it one bit.

I’ve long been a fan of checklists, indicies, bibliographies, literary guides, and genre studies. From Lovecraft’s Supernatural Horror in Literature to E.F. Bleiler’s Guide to Supernatural Fiction, and many more besides. One can spend hours immersed in these books, discovering new avenues for exploration and making mental notes on obscure titles to look out for. My shelves groan with these sorts of volumes, and despite severe bowing in some places, I don’t regret it one bit. Well, I decided to do something about that. For the past few months I’ve been in the early stages of assembling an “Encyclopaedia of Irish Writers of Fantastic Literature”. Loosely inspired by E.F. Bleiler’s Supernatural Fiction Writers and Jack Sullivan’s Penguin Encyclopedia to Horror and Supernatural, my first step was to compile a list of authors who I felt in some way contributed to Irish fantastic fiction. This list includes obvious writers such as Bram Stoker and Elizabeth Bowen, but also writers who are less well known, or whose contributions might not have had such a detectable effect on their peers.

Well, I decided to do something about that. For the past few months I’ve been in the early stages of assembling an “Encyclopaedia of Irish Writers of Fantastic Literature”. Loosely inspired by E.F. Bleiler’s Supernatural Fiction Writers and Jack Sullivan’s Penguin Encyclopedia to Horror and Supernatural, my first step was to compile a list of authors who I felt in some way contributed to Irish fantastic fiction. This list includes obvious writers such as Bram Stoker and Elizabeth Bowen, but also writers who are less well known, or whose contributions might not have had such a detectable effect on their peers.

Uncertainties is an anthology of new writing — featuring contributions from Irish, British, and American authors — each exploring the idea of increasingly fragmented senses of reality. These types of short stories were termed “strange tales” by Robert Aickman, called “tales of the unexpected” by Roald Dahl, and known to Shakespeare’s ill-fated Prince Mamillius as “winter’s tales”. But these are no mere ghost stories. These tales of the uncanny grapple with existential epiphanies of the modern day, and when otherwise familiar landscapes become sinister and something decidedly less than certain . . .

Uncertainties is an anthology of new writing — featuring contributions from Irish, British, and American authors — each exploring the idea of increasingly fragmented senses of reality. These types of short stories were termed “strange tales” by Robert Aickman, called “tales of the unexpected” by Roald Dahl, and known to Shakespeare’s ill-fated Prince Mamillius as “winter’s tales”. But these are no mere ghost stories. These tales of the uncanny grapple with existential epiphanies of the modern day, and when otherwise familiar landscapes become sinister and something decidedly less than certain . . . We rushed inside and up the staircase to the second floor. We both counted the windows and then dashed back to the drive-way to count them again from the outside. The discrepancy remained and neither of us had the answer. What had once been a familiar space was now suddenly quite strange. Our home had become, in the truest definition of the word, unheimlich. However, there was one thing we were absolutely sure of: we were less certain about our house than we were before. And that’s essentially what this anthology is about, that occasional shift in perception that can leave us with an overwhelming sense of the incredible. Uncertainties is, to be exact, a volume of uncanny tales.

We rushed inside and up the staircase to the second floor. We both counted the windows and then dashed back to the drive-way to count them again from the outside. The discrepancy remained and neither of us had the answer. What had once been a familiar space was now suddenly quite strange. Our home had become, in the truest definition of the word, unheimlich. However, there was one thing we were absolutely sure of: we were less certain about our house than we were before. And that’s essentially what this anthology is about, that occasional shift in perception that can leave us with an overwhelming sense of the incredible. Uncertainties is, to be exact, a volume of uncanny tales.

Over the summer I had the pleasure of visiting Fonthill, the astonishing storybook mansion designed and built by Henry C. Mercer. Fonthill’s eccentric architecture draws thousands of visitors a year, but scant few can claim any knowledge of Mercer’s other extraordinary achievement: a slim volume of strange stories called November Night Tales. I can thank Peter Bell for my literary adventure to Fonthill — a journey of over 3,000 miles from my home in Oregon. I had not heard of Mercer until I read Peter’s article about NNT in Wormwood (issue 22). It was here that Peter extolled the originality of November Night Tales and cited it as a great lost book that begged for rediscovery. Actually, it would be more correct to say: discovery, because very few copies of the original book were printed and sold, and until Peter wrote about it nobody really gave it much thought. Always on the lookout for new discoveries in weird fiction, I immediately began my search for Mercer’s book. I was so excited about finding a copy with dustjacket on eBay for only $230 that I completely forgot that I was shamefully surfing the net at work and shouted for joy . . . loudly. After gulping down the stories, I contacted Peter because I was thinking that my company, Bruin Books, could publish a paperback version. The situation became immediately more interesting when Peter connected me with Brian J. Showers at Swan River Press. A limited run hardback would be a more fitting tribute to this elusive gem of a book. One thing led to another and a few months later I found myself walking the Mercer Mile in Doylestown. November Night Tales was securely fastened in my mind. Now it was time to immerse myself in Mercer’s physical world.

Over the summer I had the pleasure of visiting Fonthill, the astonishing storybook mansion designed and built by Henry C. Mercer. Fonthill’s eccentric architecture draws thousands of visitors a year, but scant few can claim any knowledge of Mercer’s other extraordinary achievement: a slim volume of strange stories called November Night Tales. I can thank Peter Bell for my literary adventure to Fonthill — a journey of over 3,000 miles from my home in Oregon. I had not heard of Mercer until I read Peter’s article about NNT in Wormwood (issue 22). It was here that Peter extolled the originality of November Night Tales and cited it as a great lost book that begged for rediscovery. Actually, it would be more correct to say: discovery, because very few copies of the original book were printed and sold, and until Peter wrote about it nobody really gave it much thought. Always on the lookout for new discoveries in weird fiction, I immediately began my search for Mercer’s book. I was so excited about finding a copy with dustjacket on eBay for only $230 that I completely forgot that I was shamefully surfing the net at work and shouted for joy . . . loudly. After gulping down the stories, I contacted Peter because I was thinking that my company, Bruin Books, could publish a paperback version. The situation became immediately more interesting when Peter connected me with Brian J. Showers at Swan River Press. A limited run hardback would be a more fitting tribute to this elusive gem of a book. One thing led to another and a few months later I found myself walking the Mercer Mile in Doylestown. November Night Tales was securely fastened in my mind. Now it was time to immerse myself in Mercer’s physical world. Located in Doylestown, about an hour outside of Philadelphia, Fonthill was Mercer’s personal residence. It is situated a mile from the Mercer Museum, which Mercer also designed and built and filled to the rafters with relics of early American farmers and craftsmen. I visited the museum first, hoping to get a glimpse of the famous Lenape Stone, a carved relic discovered in a newly ploughed field in 1872. The stone, now broken in half, depicts a tribe of Native Americans taking down a Wooly Mammoth with spears. Mercer wrote an entire book about the finding, but it is now regarded as a forgery that was probably scratched out by a bored farm boy. When I finally found the stone at the very top level of the museum, I was disappointed by its size. It was more like a skipping stone than a tablet. Yet, forgery or not, I still want to believe in the Lenape Stone, because a carving of Indians and Mammoths struggling for supremacy in ancient America is how it should have been.

Located in Doylestown, about an hour outside of Philadelphia, Fonthill was Mercer’s personal residence. It is situated a mile from the Mercer Museum, which Mercer also designed and built and filled to the rafters with relics of early American farmers and craftsmen. I visited the museum first, hoping to get a glimpse of the famous Lenape Stone, a carved relic discovered in a newly ploughed field in 1872. The stone, now broken in half, depicts a tribe of Native Americans taking down a Wooly Mammoth with spears. Mercer wrote an entire book about the finding, but it is now regarded as a forgery that was probably scratched out by a bored farm boy. When I finally found the stone at the very top level of the museum, I was disappointed by its size. It was more like a skipping stone than a tablet. Yet, forgery or not, I still want to believe in the Lenape Stone, because a carving of Indians and Mammoths struggling for supremacy in ancient America is how it should have been. The stretch of road between museum and house is known as the Mercer mile, and there is a firm connection, both physically and spiritually, between the two massive structures. The quirky collection within the museum makes for an intriguing afternoon, but Fonthill is the true gem of the Mercer Mile. The house stands like a giant sand castle atop a gentle sloping hill. Mature columns of gnarled sycamore trees align a narrow asphalt road up to the house. I was there on an oppressively hot and humid day in July. A native of the west coast, I naturally associated any gray day with cooler weather, but here in Bucks County the overcast served as a pressure cooker, creating a stifling steam bath that felt more like the Florida Everglades than Amish country. The slightest movement had me panting for water. The comfy air-conditioning in the museum had weakened my resolve. I wasn’t ready for this. Mopping my head as I climbed the gravel path, it was hard to imagine the heavy snowfall that would blanket the grounds in winter.

The stretch of road between museum and house is known as the Mercer mile, and there is a firm connection, both physically and spiritually, between the two massive structures. The quirky collection within the museum makes for an intriguing afternoon, but Fonthill is the true gem of the Mercer Mile. The house stands like a giant sand castle atop a gentle sloping hill. Mature columns of gnarled sycamore trees align a narrow asphalt road up to the house. I was there on an oppressively hot and humid day in July. A native of the west coast, I naturally associated any gray day with cooler weather, but here in Bucks County the overcast served as a pressure cooker, creating a stifling steam bath that felt more like the Florida Everglades than Amish country. The slightest movement had me panting for water. The comfy air-conditioning in the museum had weakened my resolve. I wasn’t ready for this. Mopping my head as I climbed the gravel path, it was hard to imagine the heavy snowfall that would blanket the grounds in winter. Tossing aside the idea of using blueprints or even taking measurements, Mercer began work on Fonthill in 1910. All he worked from was his own sketchbook. He sculpted his castle straight from his imagination using a revolutionary reinforced cement molding process. It is an artist’s creation and bears Mercer’s fascination with Moravian ceramics. He studied the process firsthand while traveling in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and now encompassing a large part of the Czech Republic. (A number of the stories in November Night Tales are situated in this ancient cauldron of myth and superstition — Stoker and Blackwood territory.) He returned home to establish the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works just down the grassy slope from Fonthill, and as my wallet will tell you: the kilns still operate today producing traditional tiles from Mercer’s original molds. Fonthill was designed to feature Mercer’s Moravian tiles. He wanted something to show potential customers. In that sense, Fonthill is a mad kind of factory showroom. Every wall, floor, ceiling and arch is a canvass for the Mercer tiles.

Tossing aside the idea of using blueprints or even taking measurements, Mercer began work on Fonthill in 1910. All he worked from was his own sketchbook. He sculpted his castle straight from his imagination using a revolutionary reinforced cement molding process. It is an artist’s creation and bears Mercer’s fascination with Moravian ceramics. He studied the process firsthand while traveling in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and now encompassing a large part of the Czech Republic. (A number of the stories in November Night Tales are situated in this ancient cauldron of myth and superstition — Stoker and Blackwood territory.) He returned home to establish the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works just down the grassy slope from Fonthill, and as my wallet will tell you: the kilns still operate today producing traditional tiles from Mercer’s original molds. Fonthill was designed to feature Mercer’s Moravian tiles. He wanted something to show potential customers. In that sense, Fonthill is a mad kind of factory showroom. Every wall, floor, ceiling and arch is a canvass for the Mercer tiles. The only way to see the interior of the house is to pay for the guided tour. Sorry, no interior photography allowed. (Had Mercer been alive he would have met you at the door, provided lunch, good conversation and a place to spend the night before returning to Philadelphia — all out of genteel generosity and good salesmanship.) The foyer features a diminutive gift shop and, thankfully, a free-access water cooler. The house was so hot that day that the shop clerk encouraged all the visitors to drink some water before the tour began. Good advice, because despite what the official guidebook states on page nine, “the cool concrete surfaces” do not “give cool respite from the summer sun.” Judging by the number of books he owned, Mercer was clearly a book lover who enjoyed natural lighting to read by. The house has dozens of enormous windows that fill the interior with warming sunshine. At the height of summer with its insufferable humidity, however, the house became a Medieval bread oven. The labyrinth of passageways and twisting staircases, intriguing as they are, don’t allow for good air circulation. Our tour guide, who entertained us with Mercer facts spiced by a droll sense of humor, had the good sense to wear shorts and sandals, and to be conveniently bald. I had on a long shirt and pants, needed a haircut and had the Starbucks’ sweats.

The only way to see the interior of the house is to pay for the guided tour. Sorry, no interior photography allowed. (Had Mercer been alive he would have met you at the door, provided lunch, good conversation and a place to spend the night before returning to Philadelphia — all out of genteel generosity and good salesmanship.) The foyer features a diminutive gift shop and, thankfully, a free-access water cooler. The house was so hot that day that the shop clerk encouraged all the visitors to drink some water before the tour began. Good advice, because despite what the official guidebook states on page nine, “the cool concrete surfaces” do not “give cool respite from the summer sun.” Judging by the number of books he owned, Mercer was clearly a book lover who enjoyed natural lighting to read by. The house has dozens of enormous windows that fill the interior with warming sunshine. At the height of summer with its insufferable humidity, however, the house became a Medieval bread oven. The labyrinth of passageways and twisting staircases, intriguing as they are, don’t allow for good air circulation. Our tour guide, who entertained us with Mercer facts spiced by a droll sense of humor, had the good sense to wear shorts and sandals, and to be conveniently bald. I had on a long shirt and pants, needed a haircut and had the Starbucks’ sweats. There are forty-seven rooms in Fonthill, no two alike. One of the first rooms we visited was Mercer’s Library. The shelves were stuffed with leather-bound books; the walls were adorned with tiles, ornate mirrors, and old photographs. The ceilings and windows were high, allowing the daylight to brighten the room. Mercer’s writing desk was one of the few wooden objects in the house. It was a simple sturdy table built into a cement alcove that was filled with cubbyholes and bookshelves fashioned of the same dark-stained wood. It was here that Mercer must have written November Night Tales, and given the fantastic nature of the book, I like to think the creaks and moans the house emitted were more inspiring than derisive to the task.

There are forty-seven rooms in Fonthill, no two alike. One of the first rooms we visited was Mercer’s Library. The shelves were stuffed with leather-bound books; the walls were adorned with tiles, ornate mirrors, and old photographs. The ceilings and windows were high, allowing the daylight to brighten the room. Mercer’s writing desk was one of the few wooden objects in the house. It was a simple sturdy table built into a cement alcove that was filled with cubbyholes and bookshelves fashioned of the same dark-stained wood. It was here that Mercer must have written November Night Tales, and given the fantastic nature of the book, I like to think the creaks and moans the house emitted were more inspiring than derisive to the task. Mercer used Fonthill to entertain the potential buyers of his tiles and pottery, and so all forty-seven rooms are smothered in decorative tiles. One room may appear to be aesthetically balanced and reassuring to the eye, only to find the adjoining room a jarring swirl of colors that makes you want to cry out, “Man, this is crazy.” Some rooms, particularly around the fireplaces, featured large tiles arranged in tableau so that they told a story in picture and form. One might find a tale from Shakespeare, or Dickens or a fairy tale. The Columbus room is distinctly beautiful with its vaulted ceiling supported by classical pillars and positively splattered with hundreds of tiles telling the story of Columbus and his adventures in the New World (but no mammoths). One of the nicer guest rooms has the story of Bluebeard encircling the wide, muscular fireplace. How pleasant, I think, to lay in the guest-bed and drowsily study the many murdered wives of Bluebeard. Another bedroom features the mischievous antics of primitive cannibals, including slow-turning spits and bone-crunching ’round the campfire. My favorite tiled tableau is from the Pickwick Papers. When I build my dream house with its wide muscular fireplace I will purchase this set from the Moravian Tile Works down the hill.

Mercer used Fonthill to entertain the potential buyers of his tiles and pottery, and so all forty-seven rooms are smothered in decorative tiles. One room may appear to be aesthetically balanced and reassuring to the eye, only to find the adjoining room a jarring swirl of colors that makes you want to cry out, “Man, this is crazy.” Some rooms, particularly around the fireplaces, featured large tiles arranged in tableau so that they told a story in picture and form. One might find a tale from Shakespeare, or Dickens or a fairy tale. The Columbus room is distinctly beautiful with its vaulted ceiling supported by classical pillars and positively splattered with hundreds of tiles telling the story of Columbus and his adventures in the New World (but no mammoths). One of the nicer guest rooms has the story of Bluebeard encircling the wide, muscular fireplace. How pleasant, I think, to lay in the guest-bed and drowsily study the many murdered wives of Bluebeard. Another bedroom features the mischievous antics of primitive cannibals, including slow-turning spits and bone-crunching ’round the campfire. My favorite tiled tableau is from the Pickwick Papers. When I build my dream house with its wide muscular fireplace I will purchase this set from the Moravian Tile Works down the hill. To build Fonthill, Mercer only had a few loyal workers to help him and one very loyal horse named Lucy, who was paid $1.75 per day, the same as the other workers. Lucy’s job was to hoist the cement up the upper levels with a rope and pulley. She is buried on the grounds, along with Mercer’s many beloved dogs. Rollo was Mercer’s favorite dog, and he is buried just beyond the wall of the Tile Works, near and old wisteria vine. His footprints can be found in cement at both Fonthill and the Mercer Museum. A life-sized bronze statue of Rollo greets visitors as they enter the museum.

To build Fonthill, Mercer only had a few loyal workers to help him and one very loyal horse named Lucy, who was paid $1.75 per day, the same as the other workers. Lucy’s job was to hoist the cement up the upper levels with a rope and pulley. She is buried on the grounds, along with Mercer’s many beloved dogs. Rollo was Mercer’s favorite dog, and he is buried just beyond the wall of the Tile Works, near and old wisteria vine. His footprints can be found in cement at both Fonthill and the Mercer Museum. A life-sized bronze statue of Rollo greets visitors as they enter the museum. Mercer’s love of animals, his desire to surround his mansion with an arboretum, his innovative use of recycled materials to build Fonthill, his artistry, his whimsy, his kindness and philanthropy place him good standing with the people of Doylestown, and with me. As I trudged down the hill to my molten rental car that was ready to welcome me with its 1,000 degree vinyl seats, I felt I knew Dr. Mercer a great deal more than when I started the day. On the back cover of the Bucks County Historical Society pamphlet entitled Henry Chapman Mercer, there shows a flattering full-length photo of the older Chapman, no doubt taken near the time of his writing The November Night Tales. The back-of-the-book blurb states that Mercer was “A Renaissance man of the early 20th century.” He was “a historian, archaeologist, collector and ceramist. He was born, lived and died in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. To many, however, his legacy is as a scholar and visionary.” Nice, but nowhere is mentioned that he was the writer of the wonderful little book of weird tales called November Night Tales. It was a great honor to work with Brian J. Showers of Swan River Press and author Peter Bell, who contributed an introduction to our new edition, to correct that omission.

Mercer’s love of animals, his desire to surround his mansion with an arboretum, his innovative use of recycled materials to build Fonthill, his artistry, his whimsy, his kindness and philanthropy place him good standing with the people of Doylestown, and with me. As I trudged down the hill to my molten rental car that was ready to welcome me with its 1,000 degree vinyl seats, I felt I knew Dr. Mercer a great deal more than when I started the day. On the back cover of the Bucks County Historical Society pamphlet entitled Henry Chapman Mercer, there shows a flattering full-length photo of the older Chapman, no doubt taken near the time of his writing The November Night Tales. The back-of-the-book blurb states that Mercer was “A Renaissance man of the early 20th century.” He was “a historian, archaeologist, collector and ceramist. He was born, lived and died in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. To many, however, his legacy is as a scholar and visionary.” Nice, but nowhere is mentioned that he was the writer of the wonderful little book of weird tales called November Night Tales. It was a great honor to work with Brian J. Showers of Swan River Press and author Peter Bell, who contributed an introduction to our new edition, to correct that omission.