I mentioned in our September newsletter that Swan River Press would be moving in October.

That hectic week is now upon us!

I will remain in Dublin, but will be moving to ÆON HOUSE, a small, Edwardian cottage in a secluded and less frequented quarter of the inner city. The house is situated between a maternity hospital and a local funeral parlour. If there is a metaphor here, perhaps it’s best not to dwell on it.

I’ll endeavour to keep on top of correspondence and orders during all of this, but the latter half of October and early November might get more complex for me, so I would be grateful if you could keep this in mind should you need a response for anything.

By all means, orders are welcome whenever. I will try to get orders into the post as soon as possible, though, given the circumstances, please expect some delays. I will do my best.

So until we are settled . . .

Brian J. Showers

Ranelagh, Dublin

Swan River Press

Publication Delay

Update: All pre-orders and most contributor copies will be in the post by Friday, 4 June. Thank you again for your patience. – Brian

First of all, please let me apologise for the continued delay in shipping our three recent titles: The Fatal Move, Uncertainties 5, and The Green Book 17, which were supposed to have been delivered here in Dublin by our UK printed at the end of April.

The story briefly goes like this:

Delay #1: Printer broke down

Delay #2: Ran out of cloth for binding

Delay #3: Cloth needs more time to dry

Delay #4: I was informed I need an import number

Delay #5: Printer mistakenly bound in the wrong head/tailbands

Delay #6: Erroneously asked to pay import duty on VAT except items

At each of these delays I struggled no small amount to get the issue sorted. It’s taken me a week and a half to get these books out of customs. This is all mainly down to both Brexit and the printer in the UK putting down the wrong commodity code on the export paperwork. (I actually have to pay a new surcharge levied by the printer because of all the Brexit paperwork they need to fill out.)

So the good news is, the books arrived late this afternoon, despite the damaging hands of rough delivery.

What happens now? Well, I’m going to try to take off from work next week (I have a day job) so I can process your orders faster. I estimate it will take me a week and a half to get through everything and carry loads to the post office in batches (I don’t drive).

Please please please, I beg you, please don’t write to me asking if your book has shipped yet or to let you know when it does. I’ve quite a bit to juggle at the moment and such requests will slow me down in actually getting your book in the post as quickly as possible, which is my primary aim. And besides, knowing when your book was posted will not make it arrive any faster. On the other hand, if you’re going on holiday or something and want me to hold onto your book until you’re back to receive it, please let me know.

I’ve a lot of work ahead of me. Processing orders is an entire… well, it’s an entire process. I’ve got over 1,000 books here, each of which I need to first examine for defects, to weed out any that damaged or of lesser quality. You’d be surprised (or maybe not) at what sometimes turns up. Take, for example, this copy of The Green Book 17, first out of the box, with torn pages. Then I have to emboss and hand number both The Fatal Move and Uncertainties 5, taking note of requests for certain numbers–as well as numerous other special requests such as tracking numbers. All this simply takes time and I will work through it as swiftly as time allows.

Again, I apologise for this horrendously long wait for these book. It is certainly not up to my own standards and I hope this does not reflect badly on Swan River Press. However, I fear it will not be until later in June that you’ll actually see your book(s) showing up in the post. If this proves to be an inconvenience to anyone (if a book was meant as a gift for an occasion that’s now long passed), please drop me a line and I’ll be happy to issue a refund in full. In the meantime, and much to my regret and dismay, in addition to this work I also need to find a new printer, preferably one within the EU, who can work up to the standards of quality and service we’ve come to expect.

On a more positive note, the new hardbacks are printed on heavier paper stock, and you can definitely feel this added weight in your hands. The boards of both are also printed on cloth binding, which I hope you will also like. And The Fatal Move‘s jacket is printed with a nifty metallic ink. So despite these delays, once you do get the books, I’m certain you’ll be pleased with them.

Thank you again for your continued patience.

Brian J. Showers

27 May 2021

Addendum: So I trundle into the post office today thinking, gosh, the hard part is behind me now. As it turns out, postal prices went up significantly as of yesterday. I will honour all pre-orders and absorb the extra costs, but the prices of our books may have to be reviewed in the near future. Once again you have my sincere apologies. I will do my best to come up with an affordable balance.

Swan River Press Publishing Chronology

I’ve been spending the occasional odd moment assembling a Swan River Press bibliography. I started the press in 2003, so am getting to the point when I can no longer hold all the publishing details in my head. The bibliography (intended as a forthcoming publication) is meant as much a resource for me as I hope it will be of interest to readers, collectors, and bibliophiles. The book will contain my own notes on each publication as well as insights and reminiscences from authors, editors, and artists.

I think there’s a certain personality type that’s drawn to bibliographies; we possibly share some traits with list makers. Bibliographies can be highly personal things, how they’re compiled and arranged and organised. I love reading them and I love writing them. Bibliographies tell a different type of story than the ones we publish in our books. Bibliographies tell stories about the books and sometimes what happens off the page as well. If you’re of a sympathetic mindset, please leave a comment below. What information do you like to see in a bibliography? How do you like to see them arranged? Do you enjoy reading them as much as I do? Maybe you even consider yourself a serious Swan River Press collector? I’d love to hear from you all.

I’ll try to provide links to as many items as I can, though not every publication has it’s own page on the website, in which case you can find more information here (though you might have to scroll a bit to find the title in question). Or if you’re looking for The Green Book, then here.

In the meantime, I thought I would post this very basic publishing chronology. It doesn’t include any reprints or subsequent editions (although all those will eventually be noted in the bibliography). But this is the first time I’ve arranged all of the Swan River publications into chronological order. Reading between the lines, I can see the trajectory of my own life as well as the people and projects I have been privileged enough to participate in and publish. Sometimes it’s just good to take stock of these things, you know? For what it’s worth, I hope you enjoy this list.

2003

001. The Old Tailor & the Gaunt Man (Oct. 2003)

———— Brian J. Showers

2004

002. The Snow Came Softly Down (Dec. 2004)

———— Brian J. Showers

2005

003. Tigh an Bhreithimh (Oct. 2005)

———— Brian J. Showers

2006

004. No. 70 Merrion Square: Part 1 (Oct. 2006)

———— Brian J. Showers

005. No. 70 Merrion Square: Part 2 (Dec. 2006)

———— Brian J. Showers

006. On the Apparitions at Gray’s Court (Dec. 2006)

———— Peter Bell

2007

007. Blind Man’s Box (Jun. 2007)

———— Reggie Oliver

008. The Red House at Münstereifel (Jul. 2007)

———— Helen Grant

009. Quis Separabit (Dec. 2007)

———— Brian J. Showers

2008

010. Brutal Spirits (Feb. 2008)

———— Gary McMahon

011. Ghostly Rathmines: A Visitor’s Guide (Mar. 2008)

———— Brian J. Showers

012. The Nanri Papers (Aug. 2008)

———— Edward Crandall

013. The Seer of Trieste (Dec. 2008)

———— Mark Valentine

2009

014. My Aunt Margaret’s Adventure (Jul. 2009)

———— attributed to Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu

015. Thirty Years A-Going (Oct. 2009)

———— Albert Power

2010

016. Four Romances (Jan. 2010)

———— Bram Stoker

017. On the Banks of the River Jordan (Mar. 2010)

———— John Reppion

018. Bram Stoker’s Other Gothics (Apr. 2010)

———— edited by Carol A. Senf

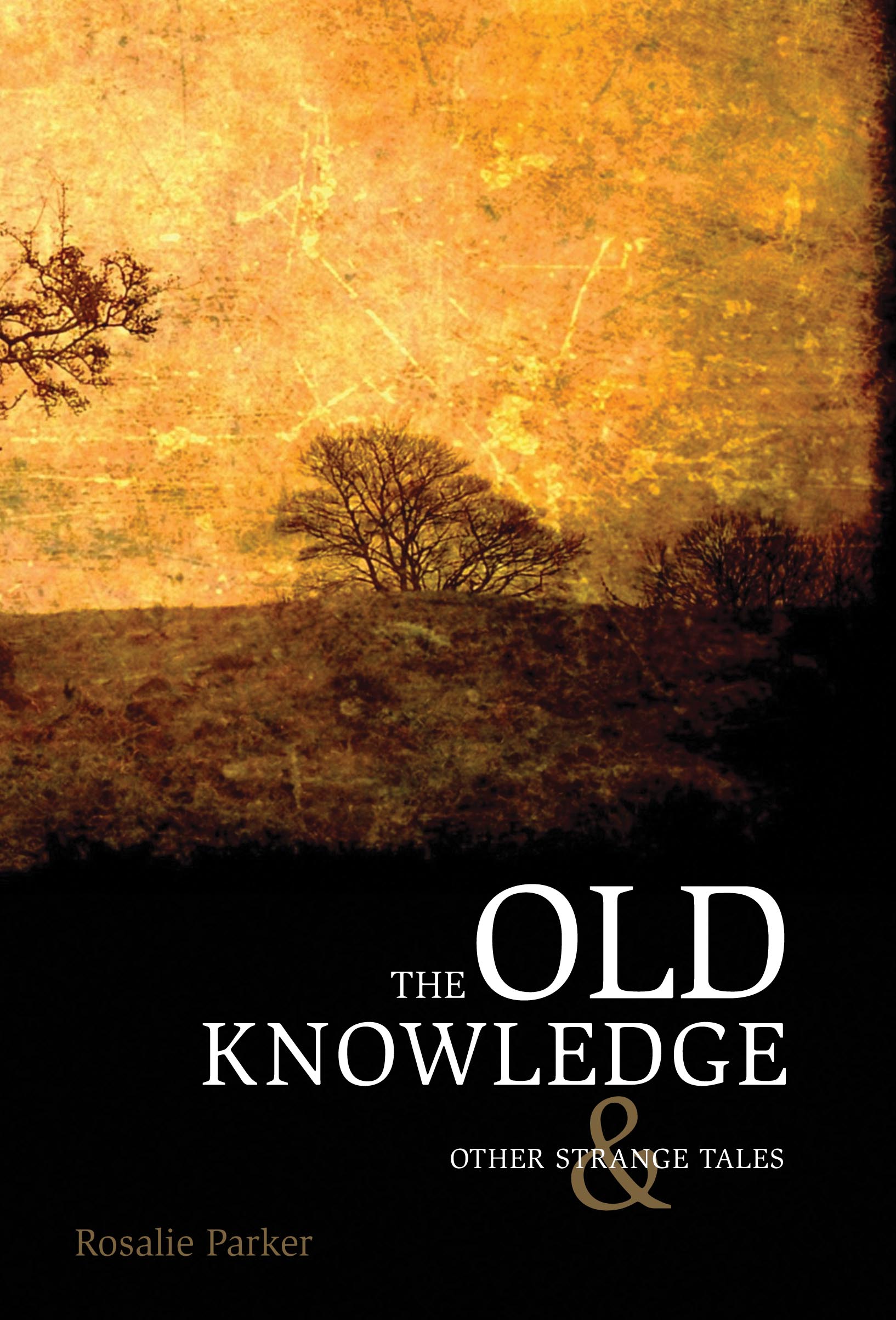

019. The Old Knowledge & Other Strange Tales (Sep. 2010)

———— Rosalie Parker

020. Extracts from Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving (Nov. 2010)

———— Bram Stoker

2011

021. Contemporary Reviews of “Dracula” (Jan. 2011)

———— introduction by Leah Moore and John Reppion

022. To My Dear Friend Hommy-Beg (Apr. 2011)

———— introduction by Richard Dalby

023. Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu: A Concise Bibliography (Jun. 2011)

———— Gary William Crawford and Brian J. Showers

024. The Ballads and Poems of J. Sheridan Le Fanu (Aug. 2011)

———— Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu

025. Curfew & Other Eerie Tales (Aug. 2011)

———— Lucy M. Boston

026. Just Like That (Aug. 2011)

———— Lucy M. Boston

027. The Complete Ghost Stories of Chapelizod (Oct. 2011)

———— Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu

028. The Definitive Judge’s House (Dec. 2011)

———— Bram Stoker

2012

029. Ghosts (Feb. 2012)

———— R. B. Russell

030. Laura Silver Bell (Feb. 2012)

———— Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu

031. Strange Epiphanies (Apr. 2012)

———— Peter Bell

032. Longsword (Jul. 2012)

———— Thomas Leland

033. Old Albert: An Epilogue (Sep. 2012)

———— Brian J. Showers

034. Selected Stories (Nov. 2012)

———— Mark Valentine

2013

035. The Sea Change & Other Stories (Feb. 2013)

———— Helen Grant

036. The Green Book 1 (Apr. 2013)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

037. Written by Daylight (June 2013)

———— John Howard

038. Seventeen Stories (Oct. 2013)

———— Mark Valentine

039. The Green Book 2 (Oct. 2013)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

2014

040. Here with the Shadows (Feb. 2014)

———— Steve Rasnic Tem

041. The Green Book 3 (Apr. 2014)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

042. The Dark Return of Time (May 2014)

———— R. B. Russell

043. The Silver Voices (Jul. 2014)

———— John Howard

044. Dreams of Shadow and Smoke: Stories for J. S. Le Fanu (Aug. 2014)

———— edited by Jim Rockhill and Brian J. Showers

045. The Green Book 4 (Nov. 2014)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

046. Reminiscences of a Bachelor (Dec. 2014)

———— Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu

2015

047. The Unfortunate Fursey (Mar. 2015)

———— Mervyn Wall

048. The Return of Fursey (Mar. 2015)

———— Mervyn Wall

049. The Demon Angler & One Other (Mar. 2015)

———— Mervyn Wall

050. The Green Book 5 (Apr. 2015)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

051. The Satyr & Other Tales (Jul. 2015)

———— Stephen J. Clark

052. The Anniversary of Never (Aug. 2015)

———— Joel Lane

053. Insect Literature (Oct. 2015)

———— Lafcadio Hearn

054. The Green Book 6 (Oct. 2015)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

055. November Night Tales (Nov. 2015)

———— Henry C. Mercer

2016

056. The Green Book 7 (Mar. 2016)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

057. Earth-Bound and Other Supernatural Tales (May 2016)

———— Dorothy Macardle

058. The Pale Brown Thing (Jul. 2016)

———— Fritz Leiber

059. Uncertainties: Volume I (Aug. 2016)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

060. Uncertainties: Volume II (Aug. 2016)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

061. You’ll Know What You Get There (Aug. 2016)

———— Lynda E. Rucker

062. The Green Book 8 (Nov. 2016)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

2017

063. Selected Poems (Apr. 2017)

———— George William Russell (A.E.)

064. A Flutter of Wings (Aug. 2017)

———— Mervyn Wall

065. The Green Book 9 (Sep. 2017)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

066. Old Hoggen and Other Adventures (Nov. 2017)

———— Bram Stoker

067. The Scarlet Soul: Stories for Dorian Gray (Dec. 2017)

———— edited by Mark Valentine

068. The Green Book 10 (Dec. 2017)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

2018

069. Death Makes Strangers of Us All (Feb. 2018)

———— R. B. Russell

070. The House on the Borderland (April 2018)

———— William Hope Hodgson

071. The Dummy & Other Uncanny Stories (May 2018)

———— Nicholas Royle

072. Sparks from the Fire (June 2018)

———— Rosalie Parker

073. Uncertainties: Volume III (Sep. 2018)

———— edited by Lynda E. Rucker

074. The Green Book 11 (Nov. 2018)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

075. The Green Book 12 (Nov. 2018)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

2019

076. Bending to Earth: Strange Stories by Irish Women (Mar. 2019)

———— edited by Maria Giakaniki and Brian J. Showers

077. Not to Be Taken at Bed-Time and Other Strange Stories (Apr. 2019)

———— Rosa Mulholland

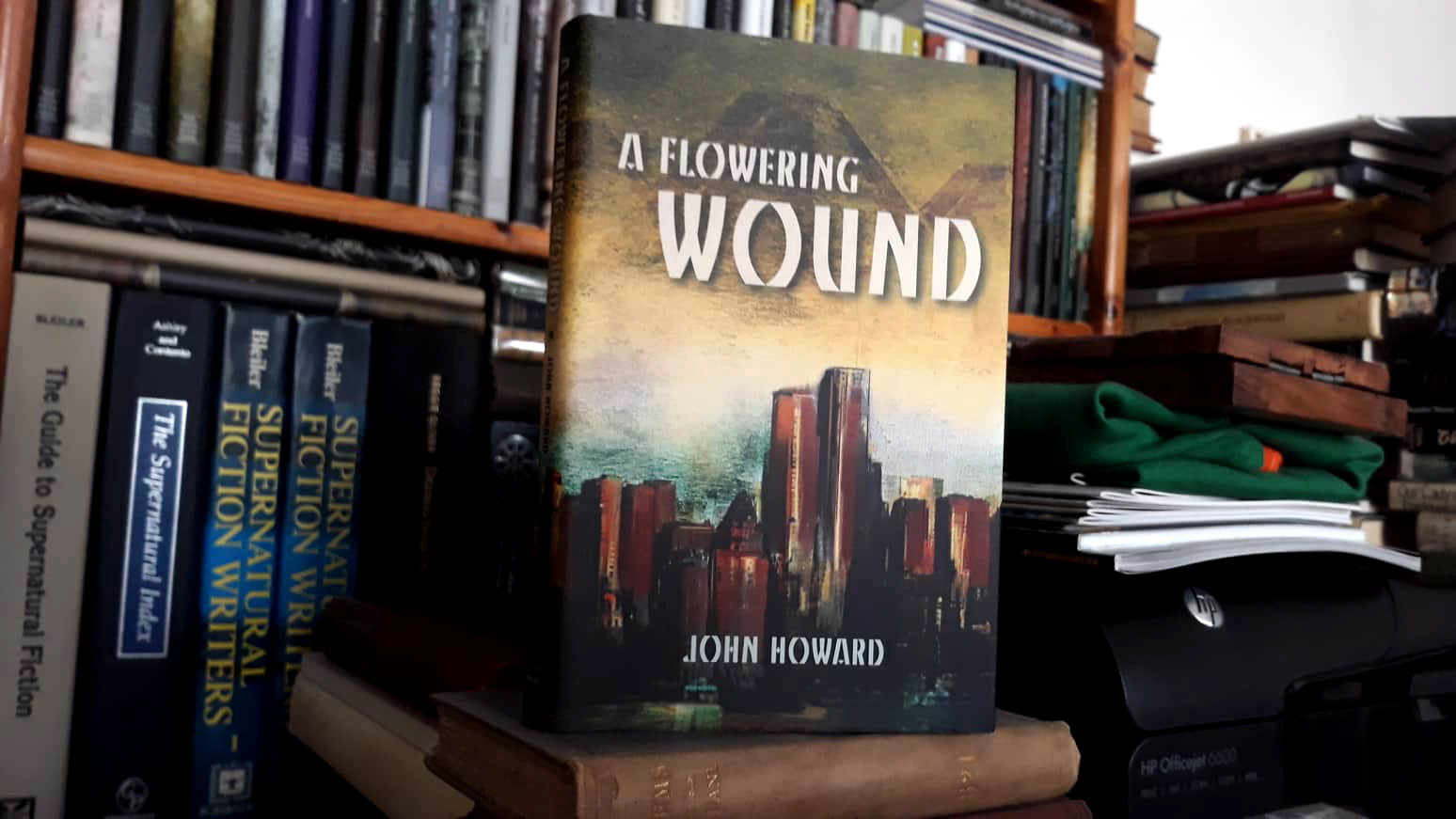

078. A Flowering Wound (Jul. 2019)

———— John Howard

079. The Green Book 13 (Jul. 2019)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

080. “Number Ninety” & Other Ghost Stories (Aug. 2019)

———— B. M. Croker

081. Green Tea (Oct. 2019)

———— Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu

082. The Far Tower: Stories for W. B. Yeats (Dec. 2019)

———— edited by Mark Valentine

2020

083. Uncertainties: Volume IV (Feb. 2020)

———— edited by Timothy J. Jarvis

084. Lucifer and the Child (Apr. 2020)

———— Ethel Mannin

085. The Green Book 14 (Jun. 2020)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

086. The Green Book 15 (Jun. 2020)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

087. Munky (Jul. 2020)

———— B. Catling

088. Leaves for the Burning (Sep. 2020)

———— Mervyn Wall

089. The Green Book 16 (Sep. 2020)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

090. The Death Spancel and Others (Nov. 2020)

Katharine Tynan

091. Ghosts of the Chit-Chat (Dec. 2020)

———— edited by Robert Lloyd Parry

2021

092. The Fatal Move (Apr. 2021)

———— Conall Cearnach

093. Uncertainties: Volume V (Apr. 2021)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

094. The Green Book 17 (Apr. 2021)

———— edited by Brian J. Showers

Our Haunted Year 2020

We can probably safely say that few could have guessed what 2020 would have in store for us. I haven’t quite decided yet whether or not I take comfort in the fact that this can be said at the start of any given year. Anyway, here at Swan River Press I had to adjust quickly: I started to work my day job from home last March, which then blurred daily into the evening hours that I put into the press. Time is a bit elastic in this room, and it isn’t uncommon to find myself wondering what day of the week it is.

Whenever I write one of these annual reviews, it seems that the most recent passing year is the “most ambitious yet”. This year feels no different, if only because most of my free moments—for better or for worse—were given over to Swan River. I suppose one must keep oneself distracted, right? I admit, I enjoy the indulgence in work. At least this sort of work.

But here we are at the end of a difficult year, and it’s time for me to take stock of what we’ve accomplished on the publishing front. I say “we” because, though it’s just been me in this room for the majority of the year, Swan River is far from just myself as you’ll quickly see.

So let’s start at the beginning.

Our first book of the year was the fourth instalment in our ongoing anthology series, Uncertainties, our showcase of new writing—featuring contributions from Britain, America, Canada, Australia, and the Philippines—each writer exploring the idea of increasingly fragmented senses of reality. This year’s volume was edited by Timothy J. Jarvis, and included an impressive line-up of stories from fourteen contemporary writers such as Lucie McKnight Hardy, Camilla Grudova, John Darnielle, Brian Evenson, and Claire Dean. I was particularly delighted to feature on the cover a painting by B. Catling, who we’ll return to in a moment. David Longhorn of Supernatural Tales had some kind things to say about the anthology: “[Uncertainties 4] has, for me, illustrated yet again the broad range of Gothic fiction, and more than hints at a genre revival in this century far more impressive than anything in the last. Perhaps this is because, like the Victorian era, ours is one of uncertain peace, irrational fads, scientific progress, and deeply unstable societies that are mirrored in confused personal identities and relationships. And people still like spooky stuff a lot.”

Lucifer and the Child by Ethel Mannin felt like one of our biggest discoveries of the year, something to be truly excited about: the first Irish edition of an overlooked novel once banned in this country. An atypical book from Mannin, Lucifer and the Child was originally published in 1945, then reviewed in the Irish Times as “a strange, but gripping book”. Our new edition of this extraordinary novel features an introduction by Rosanne Rabinowitz, and was given favourable notice in the Dublin Inquirer: “It is not surprising that this book was deemed unsuitable for 1940s Ireland. The allure of Lucifer and the occult would certainly have been deemed inappropriate, as would the depictions of female sexuality.” (Although no records exist that give reason, I personally suspect it wasn’t the occult themes that got the book banned, but rather the mention of abortion.) Despite the challenges it poses to conservative pearl-clutchers, this book was warmly received as evidenced by the many emails I got from delighted readers. The cover is by Australian artist Lorena Carrington—she did a wonderful job of depicting the dark faerie tale within its pages.

(Buy Lucifer and the Child here.)

Our next title, Munky, allowed us not only to work with artist and novelist B. Catling RA, author of the Vorrh trilogy, but for the cover art the opportunity to team up with artist Dave McKean. This project started as a submission to Uncertainties 4, but after some consideration, we decided it stood better on its own. Munky is a quirky novella that illustrates an English town and its inhabitants, as ridiculous as they are quaint, evoking an atmosphere that “might be called M. R. James with a soupçon of P. G. Wodehouse and a dash of Viz” (The Scotsman). We had also arranged for this edition to be signed by both author and artist, making this book one helluva package. Once a book is published, I tend not to go back and read it (yet again). Not so with Munky. Over these past months I found myself picking it up on occasion to revisit Catling’s charmingly cracked world.

Our fourth book this year was also our fourth by Irish author Mervyn Wall: Leaves for the Burning, originally published in 1952. We’ve been championing Wall’s work for quite some time now: The Unfortunate Fursey (2015), The Return of Fursey (2015), A Flutter of Wings (2017), and in a few issues of The Green Book. A mid-century portrait of Ireland, Leaves for the Burning is rich in grotesque humour and savage absurdity, depicting a middle-aged public servant who works in a shabby county council sub-office in the bleak Irish midlands, mired in Kafkaesque bureaucracy and petty skirmishes with locals. Although we stray from our typical fantastical themes with this one, we hope you’ll still give it a chance. With an introduction by Susan Tomaselli, editor of gorse, we are proud to make available again Mervyn Wall’s great “half-bitter book”—as it was judged by Seán O’Faoláin—surely now just as relevant as it was over half a century ago. The cover art for this one is by Niall McCormack, whose work will be recognisable to those who read Tomaselli’s gorse.

(Buy Leaves for the Burning here.)

Continuing with our “recovered voices” of Irish women writers of the supernatural, this year we published The Death Spancel and Others by Katharine Tynan. Research for this project started over three years ago—though you’ll recall we featured Tynan in Bending to Earth: Strange Stories by Irish Women (2019) and in various issues of The Green Book. Consisting of fifteen stories, seven poems, three appendices, and an introduction by Peter Bell, The Death Spancel is the first collection to showcase Katharine Tynan’s tales of the macabre and supernatural. It is also the only volume of this once-popular Irish author’s work currently in print, perhaps making this book all the more important. The Death Spancel was reviewed in Hellnotes by Mario Guslani to be “of remarkably high literary quality . . . a great collection recommended to any good fiction lover.” Brian Coldrick, who is quickly becoming one of our favourite artists to work with, did the cover for this one. You might recognise his work from the cover of Rosa Mulholland’s Not to Be Taken at Bed-time (2019).

The final hardback of the year was Ghosts of the Chit-Chat, edited by actor and scholar Robert Lloyd Parry. The book is as much an anthology of stories and poems as it is a work of scholarship. Lloyd Parry introduces each author with a short biographical sketch, building a portrait of those in the orbit of M. R. James, who debuted his own ghost stories on the evening of Saturday, 28 October 1893, Cambridge University’s Chit-Chat Club. Like many of our books, this one was long in the works. In addition to reprinting numerous rare and only recently discovered pieces, Ghosts of the Chit-Chat also features earlier, slightly different versions of James’s “Canon Alberic’s Scrap-book” (here titled “The Scrap-book of Canon Alberic”) and “Lost Hearts”. We also had a Zoom launch for Chit-Chat, and though it wasn’t recorded, we’ve got a video of Lloyd Parry reading Maurice Baring’s “The Ikon”. The volume was published on 8 December, and proved to be so popular that the already extended edition of 500 swiftly went out of print on 20 December, breaking some sort of record for us. Reception has been encouraging, with James scholar Rosemary Pardoe noting, “People who’ve missed out on it should be kicking themselves.” But don’t worry. We have plans for a paperback edition next year—sign up to our mailing list if you want advance notice.

(Buy Ghosts of the Chit-Chat here.)

We also published three issues of our journal The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and the Fantastic. Issue 14, outstanding from 2019, was published simultaneously with Issue 15. Based loosely around the theme of memoir and biographical sketches, Issue 14 contained pieces by or about Dorothy Macardle, Fitz-James O’Brien, Rosa Mulholland, among others. Issue 15 was a departure from our standard practice: we decided to feature fiction, and so reprinted rare pieces by Conall Cearnach, Herbert Moore Pim, Robert Cromie, and others. Issue 16 featured ten entries from our (still tentatively titled) Guide to Irish Gothic and Supernatural Fiction Writers project, including profiles of Edmund Burke, L. T. Meade, Forrest Read, Elizabeth Bowen, and more. Our issues for 2021 are already coming together nicely.

And there you have it!

So is anyone interested in the final tallies? I’ve got my nifty spreadsheets set up to spit out some figures. We published 8 new titles this year, totalling 1,584 pages, 2,950 copies, and 462,763 words.

Naturally we attended no conventions this year, either online or in person. I think the last might have been FantasyCon in Glasgow. But I look forward to seeing everyone again soon!

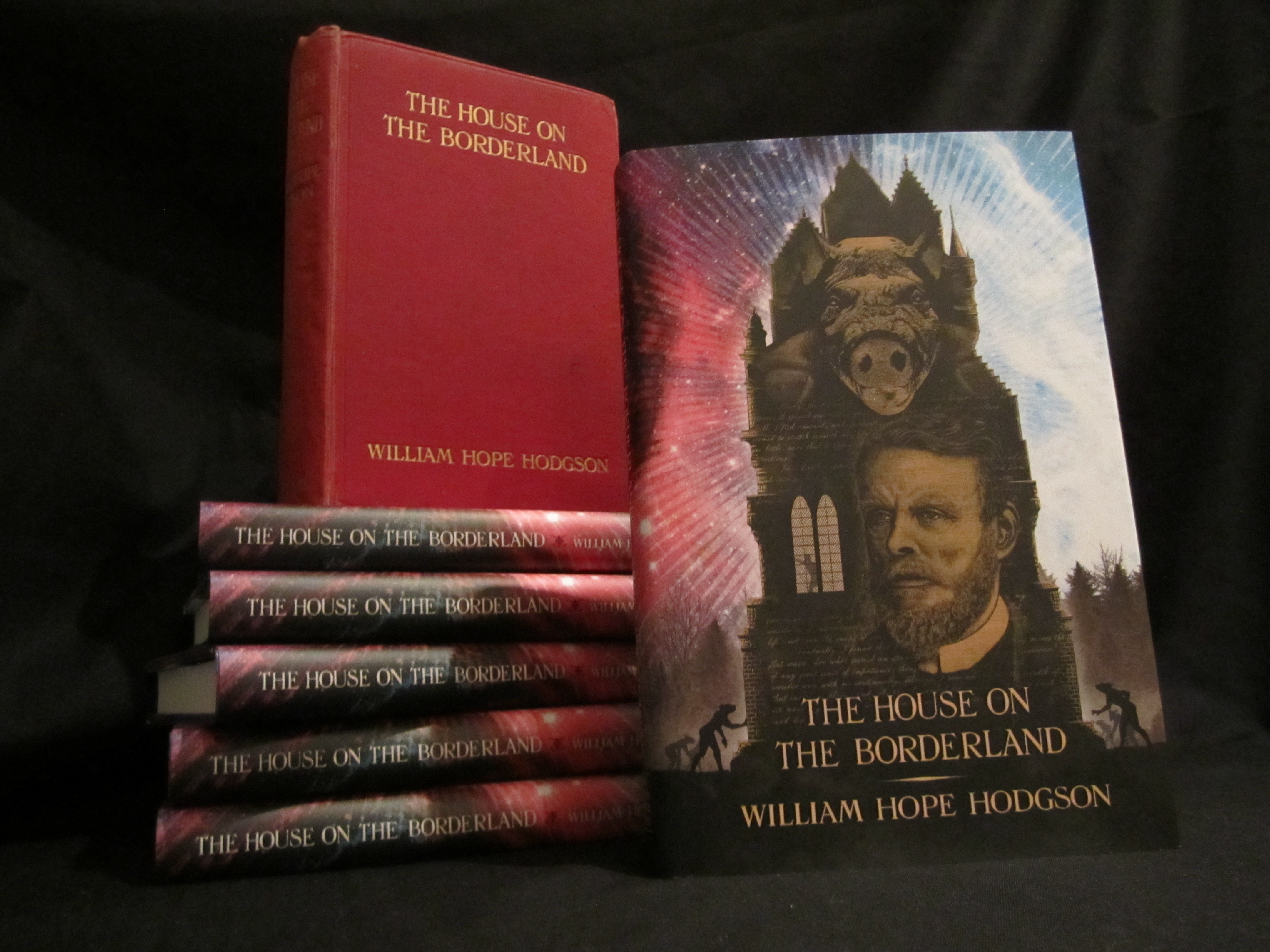

Perhaps the biggest Swan River development over these past twelve months was a long-mooted foray into paperbacks. We’ve dipped our toes in the water so far with Earth-Bound (Dorothy Macardle), The House on the Borderland (William Hope Hodgson), and Insect Literature (Lafcadio Hearn). We’ll be doing more in 2021, so it will be your chance to read some of our out-of-print books at a more reasonable price than what you’ll often find them for on the secondhand market. The reason it took so long is because I wanted to make sure we were doing paperbacks as best we could given the myriad challenges I had to consider and balance. This not only includes the books themselves, but also the behind-the-scenes admin work they create. But I’m happy we’ll been able to make available again some great stories. If you want to read more about our paperbacks, I wrote an entire blogpost about it.

(Buy Swan River Paperbacks here.)

Next I’d like to extend a warm welcome to Timothy J. Jarvis, who will be joining (actually, already has) the Swan River team. I’ve known and worked with Tim for a good many years now. I’ve always found both his fiction and writings on supernatural literature to be nothing but insightful; and I, as I am sure do many, value his generosity, passion, and friendship highly. If you want to check out Tim’s work, I suggest starting with his novel The Wanderer (2014). Tim also edited Uncertainties 4 this year, and his short fiction and articles can be found in innumerable anthologies. He is also co-editor of Faunus, the journal of the Friends of Arthur Machen (to which you should subscribe if you don’t already). Welcome, Tim!

Not forgetting the Swan River team, who make sure that I’ve not sat alone in this room for the year: Meggan Kehrli, who has once again done a superb job designing and laying out all our titles (including the various other ads and graphics I occasionally need); Jim Rockhill, who is always at the ready to provide proofreading and sage editorial input, always backed with his thoughtful scholarship; and Ken Mackenzie, who takes care of all our books’ insides, always patiently putting up with my dithering until things are just right. And finally, Alison Lyons and the team at Dublin UNESCO City of Literature, who continues to give their support, encouragement, and enthusiasm for our on-going work, allowing us to reach just a bit further than we might otherwise be able to.

(Don’t worry, I’m nearly finished.)

This year has been difficult for many, and I’ve had a lot of books and media to keep me company lately. I’d like to give a shout out to the creatives whose work I’ve been enjoying lately. Maybe you’ll find something new and interesting too: Tartarus Press, Zagava, Ritual Limited, Egaeus Press, Sarob Press, Side Real Press, Supernatural Tales, Hellbore, Nunkie Productions, Eibonvale Press, Undertow Publications, Nightjar Press, Friends of Arthur Machen—all of these people are doing the sort of things that I love, so be sure to give them your support if you find something you like. Not to mention the many booksellers out there who stock our books—and even if they don’t, be sure to support your favourite local, independent booksellers anyway. Choose to put your money into their pockets instead of Am*zon’s, because it really does make a difference.

Lastly, thank you to everyone who supported Swan River Press this year: with kind words, by buying books, donating through our patron programme, or simply spreading the word—I’m grateful for it all! If you’d like to keep in touch, do join our mailing list, find us on Facebook, follow on Twitter and Instagram. We’ve got some exciting projects for next year that I’m looking forward to sharing with you all. Until then, please stay healthy; take care of each other and your communities. I’d like to wish you all a restful holiday season, and hope to hear from you in the New Year!

Thoughts on Small Press #5—Don’t Cut Corners

My involvements with small presses have so far been only as a customer, and I’ve yet to have a really bad experience in dealing with any of them—just the occasional delay in shipment, usually for production reasons. Maybe I’ve been lucky, or I just have good taste in small presses. 🙂

My involvements with small presses have so far been only as a customer, and I’ve yet to have a really bad experience in dealing with any of them—just the occasional delay in shipment, usually for production reasons. Maybe I’ve been lucky, or I just have good taste in small presses. 🙂

The most annoying issue I’ve had with some small presses (not SRP) is poor proofreading and typography. I’ve seen books where the text was obviously scanned and OCR’d but never proofread at all, with errors on nearly every page, sometimes making it difficult to be sure what the author actually wrote. I’ve seen books with such narrow margins that the text extended nearly into the gutter (which is particularly bad with paperbacks, since it requires putting stress on the spine to spread the pages far enough apart to read everything). SRP’s books, in contrast, are a pleasure to read: comfortable to hold, well designed, and proofread so well that in my entire shelf of SRP titles I think I have found only two or three typos.

The time-consuming labor of proofreading seems like it would be a huge burden for a one- or two-person small press. One question I have for you is, how would you characterize the time and attention you put into making your books as error-free as possible? Or does your typesetter friend Ken take on most of that work? – Craig Dickson

I apologise it’s taken me so long to get to your question, Craig, which is definitely a good one! Angie McKeown asked a related question:

Could you talk a little about this high-end finish as it relates to your planning and logistics (are there things that are different than if you were producing cheaper books for example), and how it has impacted on your up-front costs and if you pitch your brand differently because of it.

I’m going to take my usual meandering approach in my response. As with so many of these questions, the answer is intertwined with myriad other thoughts. But hopefully I’ll keep such crowding to a minimum and try to answer your questions as best I can.

I can’t remember now which book it was, but it was one of our earlier ones. It might have even been Rosalie Parker’s The Old Knowledge (2010), which was our first hardback. Anyway, I’d sent a review copy to a well-respected editor. They wrote me a nice response, generally complementing the book’s production values. But there was one element that they singled out for praise: running headers. For those who don’t know, the running headers appear at the tops of the pages and usually display the book title, story title, author’s name, or a combination of these things. Grab a book nearby and have a quick look to see if it has running headers. (See if you can find one without them—which do you prefer?)

If you ask me, I think running headers in a book much improve the publication. Are they strictly necessary? Nope. Not in the slightest. You can read a book without running headers with no trouble at all. But do they make the book smart? Absolutely.

Let’s look at another example Craig brought up in his question: page margins. Have you ever seen a book that squashes as many lines onto the page as possible? You can delete the running header and gain a couple of lines. You could also expand the type area to the edges of the page and fit even more text in. Decrease the typeface and you can cram in still more text per page. Why do this? Well, for one, a book with fewer pages is cheaper to produce and therefore cheaper to buy, right? But is the reading experience at all comfortable? Does it show the text the respect it deserves? Probably not. For me, margins frame the print area so that the text doesn’t overwhelm the eye. So while margins don’t have to be as wide as six-lane highways, just don’t skimp. It can look amateurish. (Sorry, but I think it’s true!)

Designing a book is a skill—one that not everyone who publishes books takes the time to cultivate or, sometimes, even consider. My own approach to publishing is this: don’t cut corners. So much work goes into these creating Swan River Press books. As a publisher, it’s part of my job to communicate to the author that I respect their words; and to readers that their time and experience are equally valuable. One doesn’t do that with the publishing equivalent of austerity measures. My goal is always to make the best book I can. Another way to put this, and to steer this answer more toward Angie’s question: in for a penny, in for a pound.

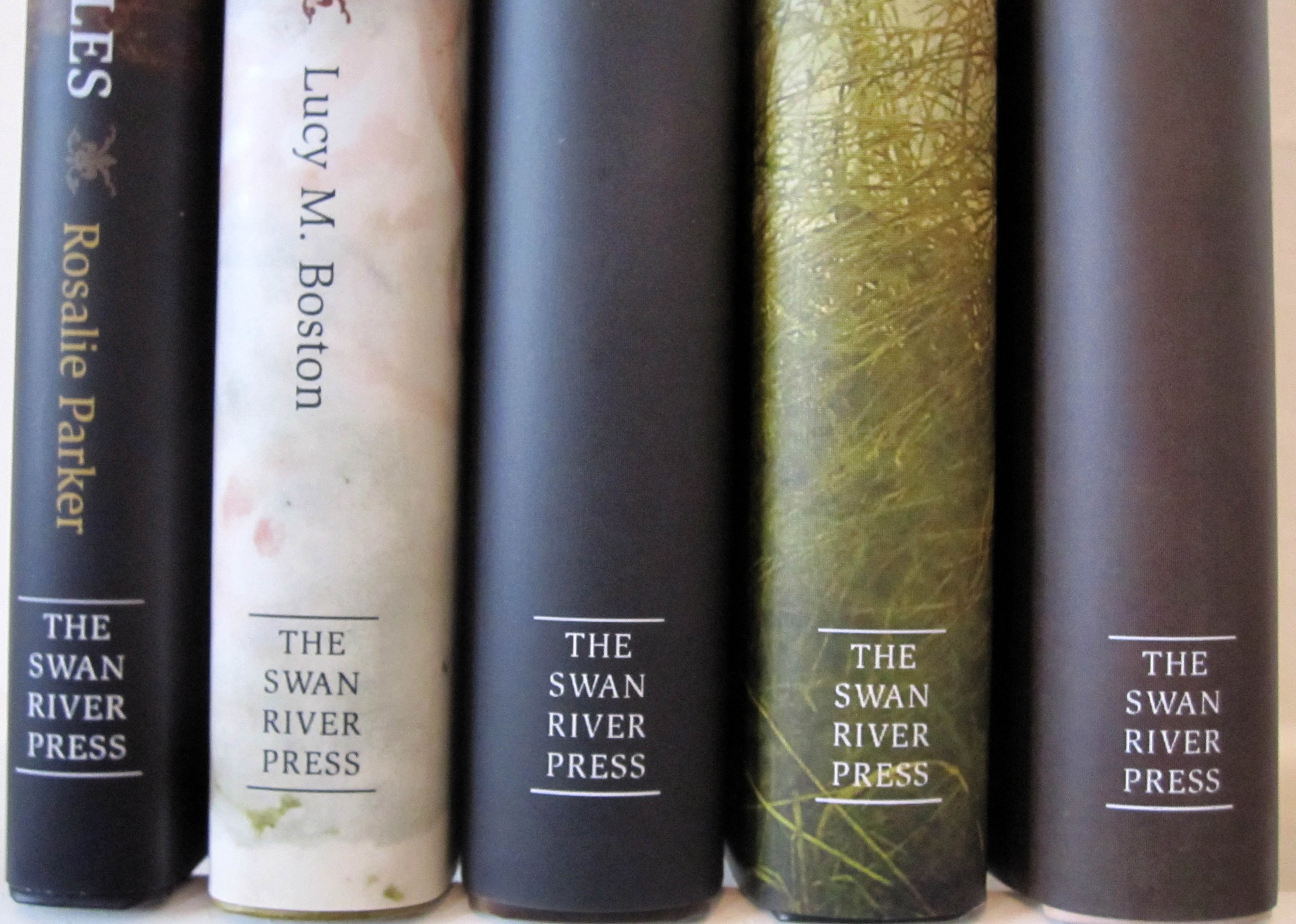

These days just about anyone can put text into a pdf and upload the file to a print-on-demand service provider. The effort required can be minimal. For some people that’s fine—so long as the words get out and into the world, the medium is of no concern. I’ve chosen to define Swan River a little differently. I want readers to feel that they’re getting something of quality, something that’s gone through a considered process in which deliberate design decisions have been made. I do this by investing money into production values. This includes things like sewn-binding, lithographic printing, and those lovely head- and tail-bands. My hope is when someone picks up a Swan River book, they will get a sense pretty quickly that it’s not a mass market production.

There are other expenses too. As Craig mentioned, there’s also proofreading. And as Craig also hints, lack of proofreading is a common enough pitfall in the small press. Swan River is not a one-person operation. While I usually give all the texts a first-pass edit and proof, Jim Rockhill is our formal proofreader. Sometimes I’m embarrassed at what I miss when he returns a text to me, but that just makes me all the more grateful for his services and expertise. I’ve learned that a second set of eyes is crucial. A trained second set of eyes is indispensable—and will cost you. Oof, I know! But again, don’t cut corners. (Certainly the odd typo will sneak through—I spotted one the other day in The Green Book 13 that I hadn’t caught!! Let us never speak of it again.)

Similarly, Ken Mackenzie does all our typesetting—keeping those running headers in order and the margins pleasingly spacious; while Meggan Kehrli does all our design work, including choosing those head- and tail-bands. Ken is far better at typesetting than I ever will be. Meggan’s design sensibilities and training would run circles around my feeble attempts any day of the week. Of course it would be cheaper to do it myself, but, ladies and gentlemen, you do not want me designing book covers. A smart publisher will find good people to work with and pay them. It’s worth it in the long run. Trust me. Don’t cut corners.

This obviously has an impact on up-front costs, as Angie rightly points out. It’s definitely not easy, and one of my future posts will more directly address financing—a subject I’ve been dancing around since the start of this column. Finding readers and building a customer base is also extremely difficult. Suffice to say, I prefer long-term investment in quality as opposed to cheaper and faster. In fact, there are some titles in our catalogue that are losing money. Not because they don’t sell, but because I’ve decided to dump so much money into their production. Our recent sesquicentenary edition of Green Tea (2019) is an example of this. It’s illustrated, comes with a specially commissioned audio adaptation of the story, plus a bunch of postcards. I’ve no regrets about this at all—the book came out exactly as I wanted it to. Design is one of the things that sets Swan River Press apart from the others, and readers who do find their way to us appreciate that. Plus it’s also something of which I can be proud.

This obviously has an impact on up-front costs, as Angie rightly points out. It’s definitely not easy, and one of my future posts will more directly address financing—a subject I’ve been dancing around since the start of this column. Finding readers and building a customer base is also extremely difficult. Suffice to say, I prefer long-term investment in quality as opposed to cheaper and faster. In fact, there are some titles in our catalogue that are losing money. Not because they don’t sell, but because I’ve decided to dump so much money into their production. Our recent sesquicentenary edition of Green Tea (2019) is an example of this. It’s illustrated, comes with a specially commissioned audio adaptation of the story, plus a bunch of postcards. I’ve no regrets about this at all—the book came out exactly as I wanted it to. Design is one of the things that sets Swan River Press apart from the others, and readers who do find their way to us appreciate that. Plus it’s also something of which I can be proud.

So I hope I’ve answered your questions, Craig and Angie. Thank you again for taking the time to ask, and let me know if there’s anything you’d like me to clarify. Naturally all of the above waffle is simply how I do things. It’s what has worked for me for the past decade or so. If you’re a publisher or self-publisher with a different approach or alternate goals, I’d love to hear from you in the comments below.

Finally, if you’re interested in Swan River Press’s design methods, have a look at this previous post in which I lay out how we put together Insect Literature (2015)—possibly one of my favourite books to work on.

Finally, if you’re interested in Swan River Press’s design methods, have a look at this previous post in which I lay out how we put together Insect Literature (2015)—possibly one of my favourite books to work on.

If you liked this post, have a look at the rest of our Thoughts on Small Press series.

My inaugural post for this series of posts is here. As always I can be contacted by email, Twitter, Facebook, or in the comments below. Please share this post where you think is appropriate. I’m looking forward to hear from you!

Did you enjoy his post and want to support the press? Check our titles in print—you might find something interesting!

-Brian

Our Numbered Editions

One of the things newcomers to Swan River Press might overlook are our numbered editions—and how they might go about getting one of them.

One of the things newcomers to Swan River Press might overlook are our numbered editions—and how they might go about getting one of them.

The first one-hundred copies of each new book is issued with an embossed stamp, hand-numbered by yours truly. Often the numbered edition comes with a similarly numbered postcard (or postcards; also usually signed by the author if that’s something I can manage, and also only while supplies last).

I believe the first book we did this for was Helen Grant’s The Sea Change & Other Stories (2013). By that point, I was casting around for ideas to make Swan River books just that much nicer for our readers, for them to be just a little more intimate and special.

I hasten to add that these numbered copies contain the same text as the “standard edition”—the sole difference is that I’ve gone at it with the embossing stamp and a bit of ink. Regardless of which edition you get, you’ll end up with the exact same text.

I hasten to add that these numbered copies contain the same text as the “standard edition”—the sole difference is that I’ve gone at it with the embossing stamp and a bit of ink. Regardless of which edition you get, you’ll end up with the exact same text.

So the question is now, how do you get one of these numbered copies?

That’s easy! First thing you’ll want to do is join our mailing list. You’ll get notifications when we announce a new book. I simply allot the numbered copies on a first-come-first-serve basis, while supplies last. And I don’t charge any extra for them either—the pre-order price for numbered copies is the exact same price I would normally charge for an unnumbered copy. If I’ve run out of numbered copies by the time you order, I’ll simply send you an unnumbered copy.

However, if I have any remaining numbered copies after pre-order, when the book is actually in print, then I tend to increase the price for the remaining numbered copies by a fiver. Or something like that!

However, if I have any remaining numbered copies after pre-order, when the book is actually in print, then I tend to increase the price for the remaining numbered copies by a fiver. Or something like that!

Do you want to collect a specific number? That’s no problem too. After you’ve ordered, just send me an email with the number you want. If it’s available, I’ll happily send that one to you, otherwise you’ll just get the next available in sequence. Keep in mind, many numbers, such as #1-15, are indefinitely claimed. But sure, it doesn’t hurt to ask and I’ll always do my best to get you the number you want.

As always, Swan River Press books in any edition are limited. In all cases, if there’s a book you want, I advise ordering it sooner rather than later, as second-hand prices on some of our books have become quite prohibitive for some.

I’ve a few numbered copies of various titles still knocking about the office at the moment—nothing extremely rare or much-sought after (just in case you’re hoping to dodge second-hand prices for books like Insect Literature or Earth-Bound). But if you’re interested in anything, do drop me a line.

Merely the Natural Plus: Lucifer and the Child

This is the story of Jenny Flower, London slum child, who one day, on an outing to the country, meets a Dark Stranger with horns on his head. It is the first day of August — Lammas — a witches’ sabbath. Jenny was born on Hallowe’en, and possibly descended from witches herself . . .

This is the story of Jenny Flower, London slum child, who one day, on an outing to the country, meets a Dark Stranger with horns on his head. It is the first day of August — Lammas — a witches’ sabbath. Jenny was born on Hallowe’en, and possibly descended from witches herself . . .

Once banned in Ireland by the Censorship of Publications Board, Lucifer and the Child is now available worldwide in this splendid new edition from Swan River Press featuring an introduction by Rosanne Rabinowitz and cover by Lorena Carrington.

Ethel Mannin (1900-1984) was a best-selling author who had written more than one hundred books but is virtually unknown today. Her output included fiction, journalism, short stories, travelogues, autobiography, and political analysis. All of her books have been out of print for decades — until now.

Born into a working-class family in South London, Mannin was a lifelong socialist, feminist, and anti-fascist. In the 1930s she organised alongside the Russian-born American anarchist Emma Goldman in support of the Spanish anarchosyndicalist forces and their struggle against Franco. Later, she agitated for the Indian independence movement along with her husband Reg Reginald. She was an advocate for African liberation movements and one of the few, even on the post-war left, who stood up for the rights of Palestinians. Iraqi critic and educator Ahmed Al-Rawi has described her as a post-colonial writer, which was unusual among British authors of the time.

In her lifetime Mannin was also known for her famous lovers, including Bertrand Russell and W. B. Yeats. In fact, it was the Yeats connection that had me trawling internet archives and second-hand bookshops while researching my tale “The Shiftings” — a ghost story exploring her relationship with the poet — for Swan River Press’s anthology The Far Tower: Stories for W. B. Yeats (2019). But I first discovered Ethel Mannin years ago, when I was a teenaged history obsessive with a special interest in labour and radical history. The figure of Mannin’s comrade “Red” Emma Goldman, described by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover as the “most dangerous woman in America”, held a powerful fascination for me. In the course of my reading I came across a vivid description of Goldman giving a speech, which was an extract from Mannin’s historical novel Red Rose (1941). This brought me to my local library looking for Mannin’s work.

While I couldn’t find Red Rose or anything about Mannin’s political activities, I did discover old editions of Venetian Blinds (1933) and Lucifer and the Child, which was first published in 1945. Venetian Blinds is a realist novel about the price paid for upward mobility, starting with the excitement of market day on Battersea’s Lavender Hill and ending with loneliness in the suburbs. It reminded me of early George Orwell novels such as A Clergyman’s Daughter (1935) and Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936), which were also about crossing class lines — albeit in the opposite direction.

After the relatively straightforward social narrative of Venetian Blinds, the ambiguous supernaturalism of Lucifer and the Child was a surprise. It is a story of witchcraft — or is it? I already had an interest in supernatural fiction but did not expect to find it in this context. Set mainly in the crowded streets of 1930s East London, the story begins when young Jenny Flower strays from a school outing in the countryside where she encounters a Dark Stranger. He could be Lucifer, or he could simply be a very imaginative and charismatic sailor.

In a passage reminiscent of Arthur Machen’s “The Great God Pan” (1894) Mannin portrays the wonder and absolute awe of a city child encountering the forest for the first time: “Sometimes there were breaks in the bird-song and then everything was very still, as though every leaf of all the millions was holding its breath and waiting, and you also waited and listened and heard your own heart beating.”

While observing a dragon-fly Jenny discovers that she is not alone. A Dark Stranger has also been watching; he steadies her as she reels in surprise at its take-off. All adults had been the enemy to her but this one is “the bringer of new things”. For the first time, she sees a life beyond her council estate, her school, and a family that does not know what to make of her. A new world opens up, one where she potentially wields power. Jenny is ushered into the “Goetic life”, a process that evokes another noted work by Machen: “The White People” (1904) in which a curious girl is initiated by her nurse into dark ceremonies and the “most secret secrets” of the countryside.

Similarly, the Dark Stranger introduces Jenny to fairy rings in the grass and tells her how the Little People made them by dancing in the moonlight. He shows her a big yellow toad under a boulder. He reveals deadly nightshade, witches’ bane, hemlock, poisonous mushrooms. He spins her tales of tree-witches and wood-spirits, nymphs and dryads, fauns and satyrs. She also comes to learn that she might be descended from two sisters burned at the stake many centuries ago.

Similarly, the Dark Stranger introduces Jenny to fairy rings in the grass and tells her how the Little People made them by dancing in the moonlight. He shows her a big yellow toad under a boulder. He reveals deadly nightshade, witches’ bane, hemlock, poisonous mushrooms. He spins her tales of tree-witches and wood-spirits, nymphs and dryads, fauns and satyrs. She also comes to learn that she might be descended from two sisters burned at the stake many centuries ago.

Jenny is a solitary child who joins in the noisy games of the other children but does not have any true friends among them. She would rather spend time with Old Mother Beadle in Ropewalk Alley. Regarded as a witch by the local children, Mrs. Beadle supplements her pension by telling fortunes and selling concoctions of herbs to induce abortions. And in this capacity, she also guides Jenny into a world of magic.

Meanwhile, Jenny’s family views Mrs. Beadle as a bad influence. So too does Marian Drew, a teacher who takes an interest in her pupil and aims to “save” her from a descent into the irrational and ultimately evil “Goetic life”. Though Marian is a vicar’s daughter she’s not entirely straitlaced. She holds progressive notions of educational freedom and creativity, perhaps reflective of Mannin’s interest in the Summerhill school of A. S. Neil, who advocated a libertarian education system in contrast to the more rigid teaching of the time.

Marian and the Dark Stranger form a relationship characterised by sharp physical attraction and equally intense debate. He asks Marian: “Do you really know where reality ends and fantasy begins? Are you quite sure that the images of your mind have no reality?” Indeed, themes regarding the transcendent and the commonplace run throughout the novel, and at one point he says to Marian: “Another drink and you may begin to understand that the supernatural is merely the natural plus.”

Lucifer and the Child is the only full-length work of speculative fiction from Mannin, who usually described herself as an atheist and rationalist. However, she was also a journalist, a seeker of curiosities and always keen to investigate. In one of her many volumes of autobiography, Privileged Spectator (1939), Mannin recollects a visit to a swami that Yeats admired. “For my part I was willing to try at least once my vibrations on a higher plane.” She gives a scathing account of her meeting with a well-fed, well-dressed individual expounding on the virtues of poverty. She had little time for mysticism or the pomp that often surrounded it.

Yet a powerful charge of the numinous and strange runs through Lucifer and the Child, despite its realism — or possibly because of it. Like Machen, Mannin also takes inspiration from London itself as well as the natural world. “Its interminable greyness and its high dockyard walls can make it as oppressive as a prison, but it has its moments — the occasional crumbling grace of a Georgian doorway, the sudden impression of a ship crossing the road as it moves into a basin, the unexpectedness of a lamp bracket jutting from a wall, of a capstan marooned in an alleyway, of funnels thrusting up at the ends of streets, and always the smell of the river with its faint, fugitive hint of the sea.”

Within this evocative cityscape we find a toad that is “strange and unknowable, like the moon” and step into Mrs. Beadle’s house: “Ordinariness stopped outside. The dilapidated door opened on to a new world. The world to which she belonged.” And in one of his arguments with Marian, the Dark Stranger suggests how the “spirit of the past” haunts people and places; a kind of spiritualism without the supernatural that would now strike a chord with modern psychogeographers.

The novel even touches on cosmic horror: “Enchantment was for her the deep forest through which she moved with deadly nightshade in her hand and an adder at her foot; it was her head upon the shoulder of the Dark Stranger, and starless night and the hunting cry of the owl; it was earth-light on the moon and no shade from the sun, and no living thing in the desolate volcanic wastes, and loneliness unutterable, the loneliness of space and dead worlds and infinity.”

Meanwhile, a dry humour underlies much of the narrative. For example, Marian’s thoughts about two do-gooding colleagues: “She reached the point at which she felt that if either of them referred once more to ‘the paw’, when speaking of the working classes, she would scream . . . ” I also chuckled when reading about the pious antics of local “cadets” joined by Jenny’s brother Les, who dedicates himself to marching and playing trumpet with them. “At the hall the cadets learned ‘First Aid’ and ‘Signalling’; they also did ‘physical jerks’, and took turns on the parallel bars and the ropes. Before they left, Mr. Wilson, their group-captain, a pale young man who was the Sunday-school superintendent, gave them a little talk on manliness and uprightness, clean thoughts and tongues, and the avoidance of something vaguely referred to as ‘bad habits’, and then they marched home again.” Such light-hearted observations grow darker as in the story’s background fascism continues to rise and conflict engulfs the world in the “sinister year 1936, with the dress-rehearsal for the coming world-war taking place in Spain”.

Mannin had been active in groups such as Workers Relief for the Victims of German Fascism and the Spanish Medical Aid Society. Looking back from the mid-1940s — she finished writing Lucifer and the Child in 1944 — 1936 indeed must have seemed an ominous turning point. And though the novel is rooted in the everyday lives of its characters, Mannin shows us that world events are never far away. She makes this connection explicit when Marian tells the cadet captain that she disapproves of “encouraging militarism” and boys “playing at soldiers” instead of creatively expressing themselves as individuals. Marian warns: “It’s only a few steps further on in this direction before they’re wearing jackboots — actually and spiritually!”

Mannin was a contradictory woman shaped by contradictory times, a prolific writer who produced an odd and imaginative book so unlike her others. Lucifer and the Child remains a rich portrayal of inter-war London and an engaging story of a girl who sought to escape it through myth and magic. And at the end of the book, the reader is left with another question: is the Dark Stranger really so “dark” after all? Or is he instead the “bringer of light”, a source of new things and knowledge in a world beset by evil far greater than any mischief wrought by a mythological fellow with horns? In effect, Lucifer and the Child is a story about the desire for a different life than the one we’re allotted and the extraordinary measures some may take to move beyond it.

“There is never any name for the impact of strangeness on the commonplace, that je ne sais quoi that ripples the surface of everydayness and sets up unaccountable disturbances in the imagination and the blood,” Mannin writes. With this sensibility Lucifer and the Child will at last be recognised as a classic of strange fiction and a work to be enjoyed by contemporary lovers of the genre.

Rosanne Rabinowitz

March 2020

Buy a copy of Lucifer and the Child.

Rosanne Rabinowitz lives in South London, an area that Arthur Machen once described as “shapeless, unmeaning, dreary, dismal beyond words”. In this most unshapen place she engages in a variety of occupations including care work and freelance editing. Her novella Helen’s Story was shortlisted for the 2013 Shirley Jackson Award and her first collection of short fiction, Resonance & Revolt, was published by Eibonvale Press in 2018. She spends a lot of time drinking coffee — sometimes whisky — and listening to loud music while looking out of her tenth-floor window. rosannerabinowitz.wordpress.com

Thoughts on Small Press #3—How Did You Start?

1. What was the itch you couldn’t scratch that made you start Swan River Press? 2. How did you start? Was it one book that turned into a line, or was it always a plan to be a full press? 3. Did you know what was involved before you started out; did you do lots of research first, or did you just dive in and learn as you go? Would you recommend this approach to others interested in starting? – Angie McKeown

Hi Angie—Thank you for sending me your questions. In reading over them, it looks as though they can be summed up with: How did you get started? It’s a good question because I think it probably impacts my approach to how I continue to run the press to this day. I mention briefly in my first post how I got started, but I’ll expand a bit more here. And I’ll see if I can come up with any broader thoughts on running a small press along the way.

Hi Angie—Thank you for sending me your questions. In reading over them, it looks as though they can be summed up with: How did you get started? It’s a good question because I think it probably impacts my approach to how I continue to run the press to this day. I mention briefly in my first post how I got started, but I’ll expand a bit more here. And I’ll see if I can come up with any broader thoughts on running a small press along the way.

The initial Swan River Press publications were palm-sized, hand-bound chapbooks. The first one, The Old Tailor & the Gaunt Man (2003), was written as a Halloween greeting for friends and family. Wanting to create something charming and striking, I devised an excruciatingly slow printing and binding method that involved quartering a sheet of paper, folding each individual section, sewing the chapbooks together with heavy black thread, and pasting in a ribbon bookmark (which I had singed with a lighter so that it wouldn’t fray).

The story aside, these chapbooks turned out beautifully. However, the process of creating them took far more work than is practicable, something I was really only able to do once per year, and even then with considerable blistering to my fingertips. People liked them though, so I did five more—the second one, The Snow Came Softly Down (2004), I issued at Christmas time. The final chapbook, Quis Separabit (2008), I released as promotion for my first collection, The Bleeding Horse and Other Ghost Stories. I’d like to point out that Old Tailor was illustrated by Meggan Kehrli, who designs every Swan River dust jacket to this day. Subsequent chapbooks contain marvellous illustrations by Duane Spurlock (who designed our logo) and Jeffrey Roche. The chapbooks are worth picking up if you can find copies. I’m proud of them.

The story aside, these chapbooks turned out beautifully. However, the process of creating them took far more work than is practicable, something I was really only able to do once per year, and even then with considerable blistering to my fingertips. People liked them though, so I did five more—the second one, The Snow Came Softly Down (2004), I issued at Christmas time. The final chapbook, Quis Separabit (2008), I released as promotion for my first collection, The Bleeding Horse and Other Ghost Stories. I’d like to point out that Old Tailor was illustrated by Meggan Kehrli, who designs every Swan River dust jacket to this day. Subsequent chapbooks contain marvellous illustrations by Duane Spurlock (who designed our logo) and Jeffrey Roche. The chapbooks are worth picking up if you can find copies. I’m proud of them.

When I was typesetting Old Tailor, almost as an afterthought, I put “Swan River Press” on the title page. Never once did I think the press would become what it is today. This naïve approach probably worked to my benefit, as there was no pressure and it was all done for fun. As an aside, anyone interested in how I came up with the name Swan River Press, there’s an entire blog post about it.

I hope that more or less answers the first part of your question. There was no formal decision. It happened casually and without me hardly noticing. Swan River Press was mostly just borne out of an enthusiasm to create something people would enjoy. Broadly speaking, it’s this same passion that keeps me going still. While I try to run Swan River as a business, I am still driven by the urge to create publications of which I can be proud and that readers will love. Sometimes this urge comes into conflict with budgeting, but, you know, fuck it. Passion generally trumps pocket book in the Swan River office. Which isn’t to say I don’t run things professionally, but rather am guided by principles probably alien to or only dimly recognised by mass market publishing. A topic for a future post, perhaps!

I hope that more or less answers the first part of your question. There was no formal decision. It happened casually and without me hardly noticing. Swan River Press was mostly just borne out of an enthusiasm to create something people would enjoy. Broadly speaking, it’s this same passion that keeps me going still. While I try to run Swan River as a business, I am still driven by the urge to create publications of which I can be proud and that readers will love. Sometimes this urge comes into conflict with budgeting, but, you know, fuck it. Passion generally trumps pocket book in the Swan River office. Which isn’t to say I don’t run things professionally, but rather am guided by principles probably alien to or only dimly recognised by mass market publishing. A topic for a future post, perhaps!

But that’s probably one of the big keys to successful small press, and indeed any labour of love: passion. Enthusiasm will get you started, but passion is what pushes you to finish the projects you’ve begun—especially despite the odds. And while passion isn’t the only thing necessary to run a small press, it’s definitely what will carry you through those moments of difficulty, when you’re struggling to learn new skills, or slogging through aspects of the job that are simply no fun.

It’s also important to note that at this time I was (and remain) a big reader of small press. I read books published by Arkham House, Tartarus Press, Ash Tree Press, and others. I was also a fan of the Ghost Story Society’s journal, All Hallows, which, like its publisher Ash Tree, is sadly no more. However, I think from being a reader of small press, I learned to appreciate truly well-published books. Sure, they cost more money than a Wordsworth paperback, but connoisseurs of fine volumes like the feel of heavier stock, how the pages turn in a book with a sewn-binding, and even generous margins indicative of typesetting not governed by doing things on the cheap. These are some of the things that can set small press apart from mass market publishing. Maybe this answers the third part of your question: did I do any research? Absolutely!

It’s also important to note that at this time I was (and remain) a big reader of small press. I read books published by Arkham House, Tartarus Press, Ash Tree Press, and others. I was also a fan of the Ghost Story Society’s journal, All Hallows, which, like its publisher Ash Tree, is sadly no more. However, I think from being a reader of small press, I learned to appreciate truly well-published books. Sure, they cost more money than a Wordsworth paperback, but connoisseurs of fine volumes like the feel of heavier stock, how the pages turn in a book with a sewn-binding, and even generous margins indicative of typesetting not governed by doing things on the cheap. These are some of the things that can set small press apart from mass market publishing. Maybe this answers the third part of your question: did I do any research? Absolutely!

Perhaps this wasn’t necessarily what you meant by research, though, when you asked the question, but in thinking about it, it’s no less important—and perhaps bolsters what I said above about passion. Which is to say I didn’t make the conscious decision to start publishing, so didn’t do any traditional research regarding methods and markets. Instead, I think I absorbed an awful lot of knowledge and possibility through my passion as a reader. Everything else I think I learnt as I went. Possibly the most valuable asset in this “research” were the connections I made, as a reader, with publishers, writers, editors, scholars, and other bibliophiles. And because of these friendships, I had an array of amazing people who were there to answer questions, give advice, and lend support.

One thing that came about from publishing the early chapbooks is I had other writers approach me asking if I would publish their stories in this way. Knowing the amount of energy that goes into it, I didn’t think it was feasible. However, I did realise that I wanted to work with writers in more of an editorial/publishing capacity. And so was born the Haunted History Series (2006-2010). Like the chapbooks, these were hand-bound booklets containing single stories. Where the chapters were palm-sized and hand-sewn, the booklets were A5 and staple-bound. Again, the booklets were bound by hand, but it was more manageable for me. Moreover, it was a valuable first opportunity to work on stories as an editor. Also during this time I produced two more series: the Bram Stoker Series and Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu Series—A5 booklets (though these were hand-sewn) showcasing some of the research I’d been doing over the years on both authors.

One thing that came about from publishing the early chapbooks is I had other writers approach me asking if I would publish their stories in this way. Knowing the amount of energy that goes into it, I didn’t think it was feasible. However, I did realise that I wanted to work with writers in more of an editorial/publishing capacity. And so was born the Haunted History Series (2006-2010). Like the chapbooks, these were hand-bound booklets containing single stories. Where the chapters were palm-sized and hand-sewn, the booklets were A5 and staple-bound. Again, the booklets were bound by hand, but it was more manageable for me. Moreover, it was a valuable first opportunity to work on stories as an editor. Also during this time I produced two more series: the Bram Stoker Series and Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu Series—A5 booklets (though these were hand-sewn) showcasing some of the research I’d been doing over the years on both authors.

As with the chapbooks, while I was working on the booklets, I still had no ambition apart from producing publications people would enjoy. So again, I avoided too much pressure. But looking back, these booklets were a vital step between my self-published chapbooks and the hardbacks that I now publish. Thinking about it now, the chapbooks and booklets were both low risk ways of gaining experience. I had no great scheme and made no grand promises, I just did the work and enjoyed it. That’s probably important for anyone wanting to do this: enjoy it.

The final step in the evolution of Swan River Press was Rosalie Parker’s submission of The Old Knowledge & Other Strange Stories (2010), which was our first hardback book. The story basically goes like this: Rosalie had originally submitted her book to another publisher. That publisher was known at the time for steadily deteriorating business practices, and though The Old Knowledge had been announced, it languished on their forthcoming list for some time. Excited to read the book, but knowing I’d be waiting for a while, I wrote to Rosalie and asked if there was an update on its publication. Rosalie wrote back and said that unfortunately there wasn’t, but asked instead of she could submit the book to Swan River. I wrote back quickly enough saying, “I don’t really publish full length books, just booklets and chapbooks.” At which point I went and had lunch . . . and thought about it . . .

The final step in the evolution of Swan River Press was Rosalie Parker’s submission of The Old Knowledge & Other Strange Stories (2010), which was our first hardback book. The story basically goes like this: Rosalie had originally submitted her book to another publisher. That publisher was known at the time for steadily deteriorating business practices, and though The Old Knowledge had been announced, it languished on their forthcoming list for some time. Excited to read the book, but knowing I’d be waiting for a while, I wrote to Rosalie and asked if there was an update on its publication. Rosalie wrote back and said that unfortunately there wasn’t, but asked instead of she could submit the book to Swan River. I wrote back quickly enough saying, “I don’t really publish full length books, just booklets and chapbooks.” At which point I went and had lunch . . . and thought about it . . .

Once again I had no grand scheme of launching a publishing house. By this time (which was the summer of 2010) Swan River already existed solidly, with a back catalogue of some nineteen chapbooks and paperbacks. So why not add hardbacks to that list? That evening I wrote back to Rosalie and asked her to send the manuscript to me. Surely it couldn’t hurt just to have a look. I loved it. Fuck it, I thought, why not? I made the decision to publish The Old Knowledge, and just sort of kept going from there!

Would I recommend this approach to others starting out? Given that it worked for me, yeah . . . I suppose so. But honestly, it was less of an approach than a series of informal decisions that lead me to where I am today. I think the benefits of doing it the way that I did is I wasn’t overcome by overambitious enthusiasm, which can be ruinous. Instead I created a few risk-free opportunities to gain experience, and without wasting the time of too many people. I also freelanced for Rue Morgue magazine at this time—and learned a ton (thank you, Monica!!) There was no pressure on me (internal or external) to produce anything. I allowed my passion to guide me and remained true to my own instincts, guided often by the insight of close friends. Contrary to the belief of some people, small press—good small press—is not a get rich quick scheme. From 2003-2010 I destroyed my fingertips publishing chapbooks and booklets. From 2010 onward I started publishing hardbacks—and that’s when the real work began.

Would I recommend this approach to others starting out? Given that it worked for me, yeah . . . I suppose so. But honestly, it was less of an approach than a series of informal decisions that lead me to where I am today. I think the benefits of doing it the way that I did is I wasn’t overcome by overambitious enthusiasm, which can be ruinous. Instead I created a few risk-free opportunities to gain experience, and without wasting the time of too many people. I also freelanced for Rue Morgue magazine at this time—and learned a ton (thank you, Monica!!) There was no pressure on me (internal or external) to produce anything. I allowed my passion to guide me and remained true to my own instincts, guided often by the insight of close friends. Contrary to the belief of some people, small press—good small press—is not a get rich quick scheme. From 2003-2010 I destroyed my fingertips publishing chapbooks and booklets. From 2010 onward I started publishing hardbacks—and that’s when the real work began.

So there you have it, Angie! I hope I’ve answered your questions, and thank you again for sending them. Does anyone out there have any further observations they’d like to add to the above? Any publishers reading this who want to comment on what got you started and what keeps you going? Do please leave a comment below!

If you liked this post, have a look at the rest of our Thoughts on Small Press series.

My inaugural post for this series of posts is here. As always I can be contacted by email, Twitter, Facebook, or in the comments below. Please share this post where you think is appropriate. I’m looking forward to hear from you!

Did you enjoy his post and want to support the press? Check our titles in print—you might find something interesting!

Thoughts on Small Press #2—What to Publish?

Brian, here’s a question for the small press discussion; What recurring characteristics and factors do you find yourself weighing up when considering whether to publish a collection/ text? What leads up to that decisive moment? Cheers, Stephen J. Clark

Hi Stephen—At first I thought your question might be a relatively easy one to answer, and on some levels it is: I tend to know what I want to publish, generally. But the more I thought about it, the more I realised that there was quite a bit of unconscious thought and a few more overt goals that influence my decision-making.

Hi Stephen—At first I thought your question might be a relatively easy one to answer, and on some levels it is: I tend to know what I want to publish, generally. But the more I thought about it, the more I realised that there was quite a bit of unconscious thought and a few more overt goals that influence my decision-making.

Before we start, I’d like to disclose the fact that the above question comes from Stephen J. Clark, who is not only a fine writer, but also an extraordinary illustrator—you really should check out his work. It’s also worth mentioning that Swan River published Stephen’s The Satyr & Other Tales in 2015, and his artwork adorns the cover of The Green Book 14.

So now your question. Generally I think one of the strengths of small press is the ability to specialise and often take greater risks than mainstream publishers. Notice how with some of the best small presses, you more or less know what you’re going to get—and even if what you get is unexpected, you can still be assured of quality. There are small presses that focus on poetry, contemporary or experimental literature, early twentieth century pulp fiction, or in the case of Swan River Press, the broader genre of supernatural fiction. This is a mode of literature I’ve loved for as long as I can remember. I touch on the beginnings of my affection for strange and uncanny in an interview conducted by Jon Mueller in 2017.

So now your question. Generally I think one of the strengths of small press is the ability to specialise and often take greater risks than mainstream publishers. Notice how with some of the best small presses, you more or less know what you’re going to get—and even if what you get is unexpected, you can still be assured of quality. There are small presses that focus on poetry, contemporary or experimental literature, early twentieth century pulp fiction, or in the case of Swan River Press, the broader genre of supernatural fiction. This is a mode of literature I’ve loved for as long as I can remember. I touch on the beginnings of my affection for strange and uncanny in an interview conducted by Jon Mueller in 2017.

It might be obvious, but is probably worth stating, that the best small presses—those that publish books that dazzle and become the most treasured volumes in your collection—are usually driven by passion and a genuine love for what they publish. So on a basic level that decisive moment is when I have that feeling that I want to be a part of this book’s life. (Yes, books—the texts themselves—have lives. They’re conceived, written, and born; they grow through various editions. Some are seemingly immortal, some die quiet and early deaths, while others are resurrected to live their twilight years as our revered elders.)

Probably the best example of this is Swan River’s 2018 edition of The House on the Borderland by William Hope Hodgson. Hodgson’s novel, at least in our genre, is certainly a revered elder. With Borderland’s reputation already secure, there was probably no good reason for the Swan River Press edition to exist. It’s widely available in myriad cheap editions; hell, you can even read it online for free if you want. But it stands as one of my absolute favourite novels of the weird and cosmic. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve read it—to say nothing of the multiple editions of this book that I’ve collected. My shelves hold a copy of the first UK edition, the Arkham House, not to mention a rake of twentieth century paperbacks. I love The House on the Borderland.

Probably the best example of this is Swan River’s 2018 edition of The House on the Borderland by William Hope Hodgson. Hodgson’s novel, at least in our genre, is certainly a revered elder. With Borderland’s reputation already secure, there was probably no good reason for the Swan River Press edition to exist. It’s widely available in myriad cheap editions; hell, you can even read it online for free if you want. But it stands as one of my absolute favourite novels of the weird and cosmic. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve read it—to say nothing of the multiple editions of this book that I’ve collected. My shelves hold a copy of the first UK edition, the Arkham House, not to mention a rake of twentieth century paperbacks. I love The House on the Borderland.

Maybe it was inevitable that the next logical step in my mania was to publish my own edition of The House on the Borderland—and I aimed to produce the best that I could: everyone involved with the Swan River edition has a fascination with and deep passion for the book. And I think the final result exudes this enthusiasm. It’s a book I can be proud of knowing that all contributors channelled as much affection into it as they could.

When it comes to contemporary writers, I’m driven by a similar sense of passion. I admit that I am not generally open for submissions (I don’t think I could handle the deluge—this will definitely be the topic of a future post). But I’m first and foremost a reader, so I have my favourites, people whose stories I enjoy, and with whom I want to work. While I don’t want to single out anyone in particular, all you need to do is have a look at the titles by our contemporary authors and I can, hand on heart, say I put the entirely of my passion behind their work.

Now the problem with passion is, left unchecked and unguided by reality, it can be ruinous. The road to hell is paved with good intentions, right? So I’ve developed over the years a sort of unofficial mission statement for Swan River Press that guides some of my publishing decisions. And with only a limited number of titles I can produce in a year, this can leave some hopeful writers disappointed (or maybe even feeling locked out of my roster). While the most books I’ve published in a year is eight, I seem to average about six, so let’s use that as our baseline.

There are a handful guides that I employ—often not successfully! But I do usually at least consider them. First, being based in Ireland, I am uniquely positioned to champion Irish fantastical literature. This is my mandate for publishing The Green Book, our twice-yearly non-fiction journal that focuses on writings about Irish Gothic, fantastic and supernatural literature. With two issues of The Green Book per year, that leaves four slots for hardbacks. Not a lot, huh?

There are a handful guides that I employ—often not successfully! But I do usually at least consider them. First, being based in Ireland, I am uniquely positioned to champion Irish fantastical literature. This is my mandate for publishing The Green Book, our twice-yearly non-fiction journal that focuses on writings about Irish Gothic, fantastic and supernatural literature. With two issues of The Green Book per year, that leaves four slots for hardbacks. Not a lot, huh?

The second guide in my mission statement is a reasonable mix of genders. Looking back over my bibliography, this is something at which I’ve failed. Of the 41 hardback books that I’ve published to date (end of 2019), only 10 are authored or edited by women. (Of the six books I have projected for 2020, only one was written by a woman.) I could do better in this area, and it’s something I’m aware of. We fare only slightly better with gender parity in our contemporary anthologies, of which there have been six. Thus far, 38% of contributors identify as women. This will increase overall with the publication of Uncertainties 4, edited by Timothy J. Jarvis, in early 2020.