EDITOR’S NOTE by Brian J. Showers

EDITOR’S NOTE by Brian J. Showers

“Ireland’s contributions to supernatural literature has been a major one and, like its contribution to literary endeavour generally, out of proportion to the country’s small size.”

– Peter Berresford Ellis, Supernatural Literature of the World

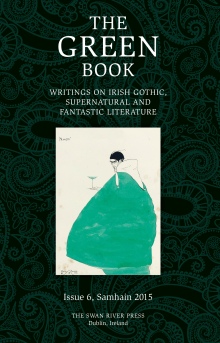

One of the occasional criticisms of The Green Book is that it’s far too niche. That the focus on Irish literature of the gothic, supernatural, and fantastic is too limiting a remit. I could never really understand this assertion, especially not now that the journal has survived twelve issues — and I’m already working on the next.

In fact, I’ve found quite the opposite to be true. The more I look at the island of Ireland’s wide-ranging and far-reaching contributions to fantastical literature, the more I learn and the more I feel excited about further exploration as both a reader and publisher; a sentiment I hope the audience of this publication shares.

So here is my reply to that occasional criticism:

The first point I’d like to make is that literature of the fantastic is incredibly broad and covers a staggering range of authors writing in myriad different modes. Lafcadio Hearn and John Connolly couldn’t be more different from each other as prose writers, and yet they are both welcome among these pages. The same can be said of Lord Dunsany and Elizabeth Bowen, or of Regina Maria Roche and Flann O’Brien — their themes, styles, and preoccupations are strikingly different. But they all belong here, each a writer who has contributed to the genres we explore in this publication.

The second point I’d like to address is — to borrow an academic word — the “problematic” notion of Irish and Irishness. Who gets to be Irish? What does it mean to be Irish? And who do we suspect — gasp! — is merely an interloper? This aspect of The Green Book is, I admit, in some sense almost arbitrary. While writers are free to choose their mode of literary expression, the exact location on the surface of this planet where they are born is nothing more than a geographical lottery. I write this as a Wisconsinite who now identifies as a Dubliner — more so than as Irish or even as American — and, believe me, I’ve been informed many times over the two decades that I have lived here that I cannot possibly be Irish. That I am a mere interloper. And yet here I sit, apparently quite inexplicably, editing this journal. (Would you believe that a Dublin-based artist, in a conversation about Francis Bacon, once told me “Bacon wasn’t really Irish, was he?” This, despite Bacon having been born in Dublin. How does one even begin responding to something like that?)

So where does that leave us?

My own approach to this dilemma — who does and who does not count as “Irish” — is simply to be as inclusive as possible, which is still no easy task, especially given the extent of Ireland’s diaspora. But I always try to fill these pages with as much interesting writing as possible.

A couple years ago Jim Rockhill (who hails from Michigan) and I decided to put together what we’re tentatively calling the Guide to Irish Writers of Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature. In Issue 11, I started publishing the fruits of this on-going project, and the present issue is filled cover-to-cover with more fascinating results.

Peter Berresford Ellis also writes in Supernatural Literature of the World, “Practically every Irish writer has, at some time, explored the genre for the supernatural is part of Irish culture”. And so I figured, if the Guide is to be of any use, and lest we include unwieldy swathes of the literary canon, it is probably best to set a few limitations, keeping in mind that these limitations might sometimes be ignored . . .

First and foremost, the Irish author in question must have contributed either substantially or uniquely to literature of the gothic, supernatural or fantastic. For example, B. M. Croker wrote enough ghost stories over her career to fill a slim volume and therefore merits inclusion for that reason; Hilton Edwards wrote and directed a single, highly notable ghostly short film: Return to Glenascaul, a strong enough achievement to merit his inclusion for at least a short entry.

Furthermore, to be considered for the Guide — and this is where things get stickier — authors should be either born in Ireland (e.g. Caitlin R. Kiernan), raised/schooled in Ireland (e.g. Lafcadio Hearn), lived a substantial or formative portion of their life in Ireland (e.g. Maria Edgeworth), or have a strong connection with Ireland through their writing (e.g. Peter Berresford Ellis).

I should probably add, with no prejudice, that mythology, folklore, and science fiction, despite the occasional overlap, not only fall slightly outside our expertise, but are already well-served in different corners by those better informed.

Even with these limitations, I estimate our Guide will clock in at a staggering 180k words. Possibly more.

Of course not everyone will agree with our definitions, nor are we asking you to. Instead, I’d like to invite you to make suggestions, naturally backed up with considered reasoning (as opposed to indignantly spitting out a name), regarding authors falling within our scope that we might have missed. Better yet, let me know if you’d like to write the entry too.

Ireland is a small island, simultaneously divided and unified, as it is, to different degrees in its various guises. But I’m constantly amazed, even if only looking at literature of the gothic, supernatural and fantastic, at the broad range of writing and the far-reaching influence that our speck of land has had on world literature. And that’s worth exploring.

You can buy The Green Book 12 here.

Contents

“Editor’s Note”

Brian J. Showers

“Jonathan Swift (1667-1745)”

Albert Power

“Charles Maturin (1782-1824)”

Albert Power

“Brinsley Le Fanu (1854-1929)”

Gavin Selerie

“Robert Cromie (1855-1907)”

Reggie Chamberlain-King

“Clotilde Graves (1863-1932)”

Mike Ashley

“H. de Vere Stacpoole (1863-1951)”

Mark Valentine

“Arabella Kenealy (1864-1938)”

Mike Ashley

“Vere Shortt (1874-1915)”

Mark Valentine

“Lord Dunsany (1878-1957)”

Martin Andersson

“James Stephens (1880/2-1950)”

Derek John

“Herbert Moore Pim (1883-1950)”

Reggie Chamberlain-King

“Mervyn Wall (1908-1997)”

Darrell Schweitzer

“Notes on Contributors”

EDITOR’S NOTE by Brian J. Showers

EDITOR’S NOTE by Brian J. Showers “A man is a very small thing, and the night is very large and full of wonders.”

“A man is a very small thing, and the night is very large and full of wonders.” Novels and Collections

Novels and Collections If you’re interested in Lord Dunsany, then you’re in luck! We’ve devoted the entirety of Issue 10 of The Green Book to Dunsany. If you’d like to read the Editorial Note and peruse the contents, please head over to our

If you’re interested in Lord Dunsany, then you’re in luck! We’ve devoted the entirety of Issue 10 of The Green Book to Dunsany. If you’d like to read the Editorial Note and peruse the contents, please head over to our  A good while back I posted the image of a poster designed by myself and long-time Swan River conspirator Jason Zerrillo. It features a line-up of Ireland’s most recognisable and possibly most influential writers of fantastic literature. I explained the impetus for the poster’s creation in an earlier

A good while back I posted the image of a poster designed by myself and long-time Swan River conspirator Jason Zerrillo. It features a line-up of Ireland’s most recognisable and possibly most influential writers of fantastic literature. I explained the impetus for the poster’s creation in an earlier