On Friday I decided to go to Mount Jerome Cemetery in Harold’s Cross, just one neighbourhood over from Rathmines, to pay respect to George William Russell (1867-1935), better known by his spiritual name “AE” (short for Aeon; simultaneously the mortal incarnation of the Logos and the representation of the immortal self). AE was a great man of a great many talents: poet, painter, novelist, economist, editor, critic, mystic, pacifist, patriot, literary facilitator, visionary—he was once (and rightfully) called “That myriad-minded man” by Archbishop Gregg (also the title of Henry Summerfield’s excellent biography). AE is largely overlooked today, perhaps because he was never recognised as a master of just one discipline. But, as AE might have joyfully observed, employing his favourite line from Whitman’s “Song of Myself”: “I contain multitudes.”

On Friday I decided to go to Mount Jerome Cemetery in Harold’s Cross, just one neighbourhood over from Rathmines, to pay respect to George William Russell (1867-1935), better known by his spiritual name “AE” (short for Aeon; simultaneously the mortal incarnation of the Logos and the representation of the immortal self). AE was a great man of a great many talents: poet, painter, novelist, economist, editor, critic, mystic, pacifist, patriot, literary facilitator, visionary—he was once (and rightfully) called “That myriad-minded man” by Archbishop Gregg (also the title of Henry Summerfield’s excellent biography). AE is largely overlooked today, perhaps because he was never recognised as a master of just one discipline. But, as AE might have joyfully observed, employing his favourite line from Whitman’s “Song of Myself”: “I contain multitudes.”

The occasion of my visit to the cemetery on 10 April was in celebration of AE’s birth in 1867. Though buried in Dublin, AE was an Ulsterman born in Lurgan, a small town in County Armagh. His family moved to Dublin in 1878, and in 1880 he attended the Metropolitan School of Art on Kildare Street where he met his lifelong friend (and occasional antagonist) W.B. Yeats. In their early days both AE and Yeats were explorers of the esoteric, but where Yeats gravitated towards the occult and the totalitarian, AE’s interests lay in the theosophic teachings of Madame Blavatsky, not to mention he was of a considerably more democratic mindset. AE originally dedicated his novel The Avatars (1933) “To W.B. Yeats, my oldest friend and enemy”, but shortly before publication shortened it: “To W.B. Yeats”.

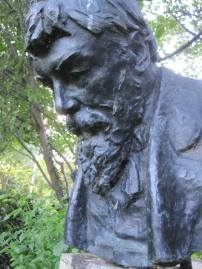

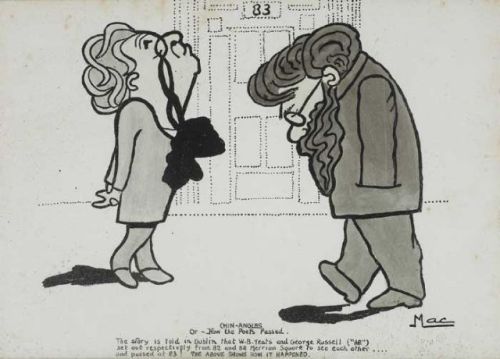

As a young man in the 1890s, AE lived in the Theosophical Society Lodge at 3 Ely Place (just a block off St. Stephen’s Green) where his mystical murals still adorn the walls. Not far from Ely Place is 84 Merrion Square, where a memorial plaque for AE can be found. It was in the upper offices of this Georgian house that AE edited the Irish Homestead (and later the Irish Statesman), the journal for the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society founded by Sir Horace Plunkett (uncle of Lord Dunsany—another of AE’s many friends). For a time Yeats lived at 82 Merrion Square, and the above cartoon entitled “Chin-angles: Or, How the Poets Passed Each Other” illustrates the anecdote of how Yeats and AE both went to visit the other, only to find they’d passed each other on the street without notice. A bust of AE can be found nearby in Merrion Square Park, head tilted as in the cartoon.

As I left my own house that morning, chin tucked against my chest, I noticed on the floor a large envelope that had been pushed through the mail slot. It contained a wonderfully synchronistic gift from that gentleman-publisher Colin Smythe: a hand-bound letterpress chapbook entitled Memories of AE by Dorothy Moulton-Mayer. I had often wondered how AE might take to certain people, and long ago concluded that he and Algernon Blackwood might have got on quite well. It was with great delight that, according to Moulton-Mayer, AE had indeed read Blackwood—she had spied a copy of The Centaur on his table during a visit. I should have known! Though had AE not read Blackwood, this is the novel I would first have lent him. Moulton-Mayer also apparently knew Arthur Machen, though I don’t suppose we’ll ever know now if she discussed the Welshman with AE. But something tells me the latter had read him nevertheless.

As I left my own house that morning, chin tucked against my chest, I noticed on the floor a large envelope that had been pushed through the mail slot. It contained a wonderfully synchronistic gift from that gentleman-publisher Colin Smythe: a hand-bound letterpress chapbook entitled Memories of AE by Dorothy Moulton-Mayer. I had often wondered how AE might take to certain people, and long ago concluded that he and Algernon Blackwood might have got on quite well. It was with great delight that, according to Moulton-Mayer, AE had indeed read Blackwood—she had spied a copy of The Centaur on his table during a visit. I should have known! Though had AE not read Blackwood, this is the novel I would first have lent him. Moulton-Mayer also apparently knew Arthur Machen, though I don’t suppose we’ll ever know now if she discussed the Welshman with AE. But something tells me the latter had read him nevertheless.

With this illuminating Blackwood connection in mind, I set off west towards Mount Jerome. Around the corner from my own residence once stood AE’s home on Mountpleasant Avenue, where he started writing The House of the Titans (a long poem he wouldn’t finish until late in life). While this house on Mountpleasant is no longer standing, his first home at 6 Castlewood Terrace is, and I passed by it just a few minutes later. However, AE’s house at 17 Rathgar Avenue, which is perhaps the home for which he is most remembered, still stands and boasts a worthy memorial plaque. During the early 20th century, this house became a Mecca for poets, politicians, novelists, artists, and various other thinkers, all seeking AE’s conversation, advice, and ever-genial hospitality: Padraic Colum, Patrick Kavanagh, Austin Clarke, Frank O’Connor, Seán Ó Faoláin, Susan Mitchell, Oliver St. John Gogarty, Jack Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Lady Gregory, Lord Dunsany, Sean O’Casey, L.A.G. Strong, Katherine Tynan, George Moore, J.M. Synge, Countess Markievicz, Francis Ledwige, Hugh Lane . . . the list is as ridiculously noteworthy as it is long. And to the twenty-year-old James Joyce, who arrived unannounced one midnight in 1902 clutching a fresh manuscript, AE said, “Young man, there is not enough chaos in your mind to create a world.” Afterwards he wrote to Lady Gregory about the visit, ” . . . [Joyce] sat with me up to 4 a.m. telling me of the true inwardness of things from his point of view.” AE eventually published three of Joyce’s stories that would later be collected in Dubliners, while Joyce went on to portray AE in Ulysses (“A.E.I.O.U.”).

Avenue, which is perhaps the home for which he is most remembered, still stands and boasts a worthy memorial plaque. During the early 20th century, this house became a Mecca for poets, politicians, novelists, artists, and various other thinkers, all seeking AE’s conversation, advice, and ever-genial hospitality: Padraic Colum, Patrick Kavanagh, Austin Clarke, Frank O’Connor, Seán Ó Faoláin, Susan Mitchell, Oliver St. John Gogarty, Jack Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Lady Gregory, Lord Dunsany, Sean O’Casey, L.A.G. Strong, Katherine Tynan, George Moore, J.M. Synge, Countess Markievicz, Francis Ledwige, Hugh Lane . . . the list is as ridiculously noteworthy as it is long. And to the twenty-year-old James Joyce, who arrived unannounced one midnight in 1902 clutching a fresh manuscript, AE said, “Young man, there is not enough chaos in your mind to create a world.” Afterwards he wrote to Lady Gregory about the visit, ” . . . [Joyce] sat with me up to 4 a.m. telling me of the true inwardness of things from his point of view.” AE eventually published three of Joyce’s stories that would later be collected in Dubliners, while Joyce went on to portray AE in Ulysses (“A.E.I.O.U.”).

Continuing across Rathmines I cut through Leinster Square and passed the former home of James Stephens (AE’s friend and protégé, and a man who definitely associated with Machen). “He inclined to sit on the top of the morning all day,” wrote Stephens of his friend’s demenour. The arrival of the chapbook earlier in the morning wouldn’t be the only fortuitous moment that day. Towards the end of Leinster  Road I decided to take a shortcut down a particularly rundown alleyway where I came across some graffiti that I think I will allow to speak for itself.

Road I decided to take a shortcut down a particularly rundown alleyway where I came across some graffiti that I think I will allow to speak for itself.

Finally Mount Jerome, with its familiar flower vendors and the red-faced man in top hat and walking stick greeting visitors at the gate. I bought a bouquet for a fiver. It was the least I could do. Naturally along the way I also stopped to visit an old friend, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu. I pulled the spring weeds from his recently restored vault and admired the memorial plaque his friends and family erected in his honour last summer.

At last I arrived at the modest grave of the man born George William Russell. In 1933, after the deaths of his wife Violet and his lifelong friend Horace Plunkett, and the recent formation of Éamon de Valera’ s government (“I curse that man as generations of Irishmen to come will curse him—the man who destroyed our country”), AE sold his house in Rathgar, left Ireland, and eventually settled in England after a lengthy lecturing tour of America.

At last I arrived at the modest grave of the man born George William Russell. In 1933, after the deaths of his wife Violet and his lifelong friend Horace Plunkett, and the recent formation of Éamon de Valera’ s government (“I curse that man as generations of Irishmen to come will curse him—the man who destroyed our country”), AE sold his house in Rathgar, left Ireland, and eventually settled in England after a lengthy lecturing tour of America.

“Dublin’s Glittering Guy” (as O’Casey once described AE) breathed his last on 10 July 1935 in a nursing home in Bournemouth. Though Yeats had not come (and only telegraphed after a long silence), Gogarty was at his bedside, as was P.L. Travers, AE’s nurse and secretary in his final days. His body was laid out at the offices in 84 Merrion Square, and a procession more than a mile long passed through Rathmines before arriving at Mount Jerome.

Here at the graveside, where I now stood, once were assembled, beside many others, AE’s son Diarmuid, his political foe President de Valera, ex-President W.T. Cosgrave, W.B. Yeats, and Frank O’Connor, who delivered the oration. The most extravagant offering of flowers came from a woman who was once a servant in the Russell household. On being questioned on the costliness of her gift, she declared “I would have died for him.”

I’d brought along my copy of AE’s Selected Poems, published shortly before his death in 1935. In the brief preface, the poet wrote, “If I should be remembered I would like it to be for the verses in this book. They are my choice out of the poetry I have written.” And from this selection I read:

Should you ever come to Ireland, there are many places you can visit to celebrate AE’s life and works, a good few of which I’ve already listed. The Hugh Lane Gallery often has one of his paintings on display, and a trip to Lissadell House in County Sligo is a must: they have the largest collection of AE’s paintings in the world. In the Armagh County Museum is another exhibition on the life and works of AE, including a number of paintings.

First editions of AE’s work can be easily procured online, and they are worth the effort. Among the prizes in my own collection are a signed copy of Enchantment and Other Poems (1930) and AE’s novel The Interpreters (1922) inscribed to Gogarty. John Eglinton’s A Memoir of AE (1937) is worth a read, as is the essay collection The Living Torch (1937) edited by Monk Gibbon. Those of a more mystical mindset might like The Candle of Vision (1919; my copy once belonged to Gibbon) or Song and Its Fountains (1932).

First editions of AE’s work can be easily procured online, and they are worth the effort. Among the prizes in my own collection are a signed copy of Enchantment and Other Poems (1930) and AE’s novel The Interpreters (1922) inscribed to Gogarty. John Eglinton’s A Memoir of AE (1937) is worth a read, as is the essay collection The Living Torch (1937) edited by Monk Gibbon. Those of a more mystical mindset might like The Candle of Vision (1919; my copy once belonged to Gibbon) or Song and Its Fountains (1932).

My sincere hope is that in the lead-up to the 150th anniversary of AE’s birth, more people will discover and appreciate his contributions to Irish art, literature, and culture.

My sincere hope is that in the lead-up to the 150th anniversary of AE’s birth, more people will discover and appreciate his contributions to Irish art, literature, and culture.

[…] If you’re looking for more Irish poetry, please check out our previous post on George William Russell (AE). […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the marvellous post on AE and evocation of the times and places in which he worked, lived and died. We have some of his paintings also in NUIG and we plan to showcase them for the 150th anniversary of his birth.

LikeLike

That sounds wonderful! Please drop me a line with the details–I’d love to come to see them.

LikeLike

Hi,

Great post.

You may be interested to know that Armagh County Museum and Craigavon Museums Services have planned a series of events over March and April 2017 to mark the 150th anniversary of the birth of AE in Lurgan.

Details can be found at:

https://www.facebook.com/Armagh-County-Museum-780806655297849/?fref=ts

https://www.facebook.com/CraigavonMuseumServices/?fref=ts

LikeLike

Thanks, David! Yes, I did know about the events–although they don’t seem to be reflected on the Armagh Museum website. On 10 April I’ll be live tweeting #AE150 a memorial walk. We’re also publishing a limited anniversary edition of AE’s Selected Poems, which should be back from the printer in a week. http://swanriverpress.ie/title_selectedpoems.html

LikeLike

I’ll certainly be ordering a copy of that. Look forward to reading your tweets.

LikeLike

[…] If you’d like to read more about A.E., please see our previous post here. […]

LikeLike

http://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/aeiou-ireland-s-debt-to-george-russell-1.3040486

Daniel Mulhall has contributed a biographical afterword to a new edition of AE’s Selected Poems, published today by the Swan River Press. He will deliver a talk on AE at the National Library at 7pm this evening. He is currently Ireland’s Ambassador in London

LikeLike

[…] If you’d like to read more about A.E., please see our previous post here. […]

LikeLike

Are there any collections of George Russell’s paintings in book form?

LikeLike

Hi Shawn, I’m not aware of any substantial art book with A.E.’s work has ever been published. There were one or two exhibition catalogues in the 1980s, and the Oriel Gallery catalogue from 1996, but I think that’s about it. He really should be serviced by something more substantial, though I think it would be a costly enough undertaking as his artwork–and there was much of it of varying quality–is quite scattered.

If you want to see a substantial selection first hand, I suggest visiting Lissadell House in Sligo.

LikeLike

He maybe a relative of mine are there any directly living relatives

LikeLike

He had two sons: Brian and Diarmuid. Brian married an American woman (whom A.E. was fond of) and moved to Chicago. Honestly, though, I’m not sure what happened to either of the two sons and have not, to my knowledge, met any Russells of A.E.’s lineage (and I’ve met Maturins, Le Fanus, Stokers, Hearns, Dunsanys, etc.) Sorry I couldn’t be of more help.

LikeLike

Thank you Imjust saw your reply now. It appears he may have been a cousin of my great grandfather Thomas Henry Russell of Lurgan

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] George William Russell (1867-1935), better known by his spiritual name “AE” (short for Aeon; simultaneously the mortal incarnation of the Logos and the representation of the immortal self). AE was a great man of a great many talents: poet, painter, novelist, economist, editor, critic, mystic, pacifist, patriot, literary facilitator, visionary. […]

LikeLike

[…] If you’d like to read more about A.E., including who he was and why he is an important contributor to Irish literature, I wrote another piece about him that you can read here. […]

LikeLike